DACF Home → Bureaus & Programs → Bureau of Parks and Lands → Discover History & Explore Nature → History & Historic Sites → Whaleback Shell Midden

Whaleback Shell Midden

A thousand years of Native American seafood dinners

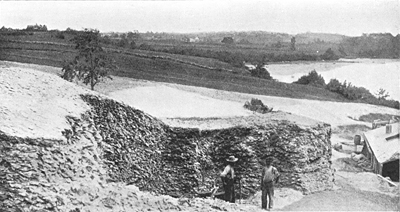

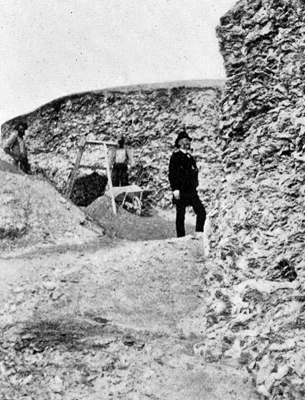

These two men are standing next to the Whaleback Shell Midden in Damariscotta in 1886. The pile of oyster shells was once more than thirty feet deep.

Shell middens (also often called "shell heaps," and "shell mounds") are rubbish dumps left by prehistoric peoples, usually in coastal areas. They consist mainly of discarded shells along with related cultural materials, such as bones, ceramic pots, and stone tools. Middens can range in size from thin scatterings of shells along the shore to deep, layered accumulations like the ones here, which have built up over many, many years.

Because of the calcium carbonate content of the shells, middens tend to be alkaline, which reduces soil acidity that otherwise quickly destroys shells, bones and other discarded materials. Animal remains may be preserved over long periods of time and their analysis gives archaeologists valuable clues as to the climate, season, hunting patterns, and other conditions existing during periods when a site was occupied. Artifacts found in middens also help archaeologists set dates for when the middens were created and better understand the technologies and way of life of the ancient peoples that built them.

Because of the calcium carbonate content of the shells, middens tend to be alkaline, which reduces soil acidity that otherwise quickly destroys shells, bones and other discarded materials. Animal remains may be preserved over long periods of time and their analysis gives archaeologists valuable clues as to the climate, season, hunting patterns, and other conditions existing during periods when a site was occupied. Artifacts found in middens also help archaeologists set dates for when the middens were created and better understand the technologies and way of life of the ancient peoples that built them.

The upper Damariscotta River is famous for its enormous oysters shell heaps, also called middens. Native Americans created the middens over a period of about a thousand years, between 2,200 and 1,000 years ago.

The east side of the Damariscotta River once contained an enormous shell heap named Whaleback because of its shape. Much of this midden was removed in the late 1880s to supply a factory built here to process the oyster shells into chicken feed. As a result, only a small portion of Whaleback remains today.

Managed in cooperation with the Coastal Rivers Conservation Trust, the area around the midden is now a State Historic Site that includes a small hiking trail and beautiful views of the river. A series of interpretive panels helps inform visitors about the history of the area.

Who Built the Middens?

There is archaeological evidence that early Indians lived, hunted, and fished on the upper Damariscotta River at least five thousand years ago, if not earlier. The people who built our great shell heaps came later, however. Archaeologists think they were ancestors of the Etchemins--who were here to meet the first European explorers in the early 1600s--and that they migrated northward into this part of the Maine area sometime between 3,000 and 2,500 years ago.

The most important innovation introduced by these new arrivals was the art of making pottery vessels designed for cooking food and other purposes. Because of this new and distinguishing skill, experts today designate the time span from roughly 2,700 years ago until the introduction of European influences in the late 1500s and early 1600s as the "Ceramic Period" in Maine's archaeological history.

Carbon tests made on shells from the middens establish that the oysters were harvested here roughly between 2,200 and 1,000 years ago. Stone artifacts and pottery fragments that have been found reflect materials, techniques, designs and decorations characteristic of several distinct stages of the Ceramic Period.

Study of the many bones found among the shells shows that the midden-builders were skilled hunters and fishermen with a well-rounded diet that included large game, different kinds of fish, and wild birds. Then as now, the annual arrival of alewives was an important event.

From analysis of the growth patterns of oyster shells, deer antlers, and other indicators, archaeologists conclude that oysters were harvested only during the winter and early spring. Then, perhaps following the annual alewife run in mid-May, the Indians apparently moved on to other hunting grounds for the rest of the year. No signs of a permanent settlement have been found.

What's Hidden in a Midden?

While searching through a midden may not seem like the most glamorous thing in the world, they do provide many clues to man's early relationship with the sea and its cultural and historical significance in their affairs. In searching through a shell midden, an archaeologist pays attention to the kinds of shells, where they were found and the fine details of their condition, often performing microscopic or chemical analysis. From these examinations, archaeologists can infer how people used the items, the value they placed on them, how they prepared them, where they collected them and sometimes, what the general climate was like in the locations where the shells were growing. Taking all these things together, archaeologists can piece together a pretty good picture of the every day life of these people.

In 1886, as preparations were being made to mine the Whaleback midden, the Peabody Museum at Harvard University purchased the rights to all prehistoric materials that were uncovered and hired Damariscotta "antiquarian" A.T. Gamage to oversee the process. Daily for six months, from June through November, Mr. Gamage labored alongside the mining workers. He carefully logged and mapped the location of items found as the shells were removed, then boxed them up and sent them to the museum.

Among his discoveries were a number of stone artifacts such as arrow and ax heads. Many fragments of broken ceramic pots, often decorated, were discovered at all layers of the shell heap. And beside oyster and other kinds of mollusk shells there were many various mammal, bird and fish bones--some from creatures that no longer exist, at least in the Damariscotta.

Along with bones of deer, moose, bears, raccoons, seals, eider ducks, and loons, Gamage discovered remains of shad, sturgeon, very large codfish, as well as of sea mink and the great auk, a flightless seabird. The latter two have both been extinct since the 1800s. He also collected alewife, eel, and tomcod bones--fish still found in the river today. Some of the oysters shells he shipped to the museum were more than a foot long!

The mining operation also uncovered the remains of at least 14 humans and several dog burials as well.

Mining Whaleback

Since European settlement, area residents have viewed the Damariscotta River's shell middens as a resource to be used. In 1692, English stone masons built Fort William Henry at Colonial Pemaquid with lime produced from Whaleback's shells. Later, residents used the shells as fertilizer and fill for roads as well as other uses.

These early uses did not compare, however, to the larger-scale industry here in 1886. Incredible as it may seem by today's preservation standards, that mining effort largely destroyed the huge Whaleback Midden to produce an additive fed to chickens to strengthen their egg shells.

The mining business, Massachusetts-based Damariscotta Shell and Fertilizer Company, built several structures here to house this work. The structures contained a fertilizer factory, mill (or grinder), dryer (including a furnace), well, and storehouse. Workers packed and shipped more than 200 tons of shells during the operation, with much of the mining apparently completed in the first year. Indeed, after only three months, Abram Gamage wrote: "The shell heap is dwindling away and after this month the grandeur of the heap will be so far gone as not to be worth going to see."

The buildings burned in 1891 and the operation was abandoned. Before the company's mining activities, Whaleback Midden extended 400 feet uphill from the river bank and was up to 15 feet deep. Afterward, only a small portion remained.