Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Mammals → Canada Lynx

Canada Lynx

Lynx canadensis

Federally Threatened, State Species of Special Concern

On this page:

- Habitat

- Diet

- Distinctive Characteristics

- Nocturnal/Diurnal

- Seasonal Changes

- Reproduction & Family Structure

- Survival & Threats

- Management & Conservation

- Research & Monitoring

- Prevent or Resolve Conflicts

Maine is home to the largest lynx population in the lower 48. They frequent the young spruce and fir boreal forests in remote northern and western regions of the state. Lynx can move long distances, but they are unlikely to be seen in southern or central Maine where bobcats are more common. Lynx prey on snowshoe hare but also eat other mammals, birds, and animal carcasses. They have large feet and long legs that make it easier to move in deep snow when compared to bobcats and other carnivores that might otherwise compete for habitat and prey.

Habitat

Lynx are common throughout the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada. The southern portion of their range once extended into the U.S. in the Rocky Mountains, Great Lakes states, and the Northeast. Today, resident breeding populations of lynx are primarily found in Maine, Minnesota, Montana, and Washington, and lynx have been reintroduced to Colorado. In the Northeast, small numbers of reproducing lynx have been documented recently in northern New Hampshire and northern Vermont, but the ability of these peripheral areas to sustain persistent breeding populations is questionable.

This forest-dwelling cat occurs in northern latitudes where deep snow and spruce/fir forests are common. In Maine, lynx are most common in the spruce/fir flats of Aroostook and Piscataquis counties and northern Penobscot, Somerset, Franklin and Oxford Counties, where snow depths are often the highest in the state. Although lynx are more common in northern and western Maine, lynx have expanded into eastern sections (northern Washington County).

Diet

Lynx are highly specialized to hunt snowshoe hare, which comprise over 75 percent of their diet when hares are abundant. Lynx consume one or two hares a day. In the summer, the diet is more varied and may include grouse, small mammals, squirrels, and animal carcasses.

Distinctive Characteristics

Although lynx are similar in size and appearance to bobcats, lynx appear larger because of their long legs. The most distinguishing characteristic of lynx is the large, densely furred feet (like snowshoes) that help them travel over snow. Both lynx and bobcats have black tufts of fur on their ears and a short, black-tipped tail, however, lynx have long ear tufts and a completely black tipped tail where bobcats have short ear tufts, and the tip of their tail is black on top and white underneath. When looking at an animal's silhouette, the hind end of a lynx is slightly raised whereas the back of a bobcat is relatively flat. Adult male lynx average about 33 1/2 inches long and weigh between 26 and 30 pounds. Female lynx are about 32 inches long and weigh between 17 and 20 pounds.

Canada lynx

- Longer ear tufts (1" or longer)

- Longer facial ruff

- Shorter and completely black-tipped tail

- Large and well-furred feet (>3" track)

- Uniform coat color

Bobcat

- Shorter ear tufts (absent to 1")

- Shorter facial ruff – more round face

- Tail black-tipped on top and white underneath

- Smaller feet (2" track)

- Less-uniform coat (white underbelly, spotted)

Nocturnal/Diurnal

Lynx are active during both day and night.

Seasonal Changes

A lynx winter coat is light gray and faintly spotted, and the summer coat is much shorter and has a reddish-brown cast to allow them to blend in better with their environment. The breeding season is late February through March, with males increasing their movements in search of mates during that time of year.

Reproduction & Family Structure

Photo credit: John Gilbert

After a 60-70 day gestation period, female lynx give birth to kittens in May. In Maine, lynx have produced litters of one to five (average of three) kittens in dens consisting of a depression under thick young fir trees or elevated downed logs. Kittens are raised by the female, who occasionally leaves the den to hunt. Kittens are able to travel with their mother by early July and stay with their mother until the following spring.

Females and their kittens (family groups) hunt together to increase hunting success. With the exception of breeding pairs and family groups, lynx are solitary. The size of a lynx home range can vary with snowshoe hare density, habitat conditions, and season. In Maine, male home ranges are 18 square miles (half a township), which is twice as large as a female's home range area. Adult female lynx share their entire range with a male and a male may share portions of his home range with one to three adult female lynx.

Survival & Threats

During the Maine lynx study (1999-2011), we documented 65 lynx mortalities. Predation and starvation were the leading causes of death for radio-collared lynx. Fisher were the primary predator, accounting for 14 of the 18 lynx mortalities from predation (McLellan et al. 2018 (PDF)). This was notable because fisher predation on lynx had not been previously documented. Lynx also die from disease, other natural causes, illegally shot, legal harvest in Canada, and vehicle collisions. From 2014-2024, we documented 49 lynx mortalities from vehicle collisions. Although Maine's lynx population is doing well, they are limited by availability of snowshoe hares and adequate snow conditions. Climate warming will likely retract lynx range northward at some point in the future.

Management & Conservation

Historically, lynx were uncommon in the northeastern United States. Currently, Maine is the only state in the Northeast with a resident breeding population of lynx, comprising the southern edge of a larger lynx population that extends into Quebec and New Brunswick. Lynx have been observed in New Hampshire and Vermont including female lynx with kittens, suggesting lynx are expanding into former parts of their historic range.

Canada lynx were federally listed as threatened in 2000 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). A joint twelve-year study of lynx revealed that the extensive cutting of spruce and fir in the 1970s and 1980s following an insect outbreak benefited lynx 25-35 years later in Maine. The abundance of young dense conifer forest became ideal habitat for snowshoe hare, the principal food source for lynx, and subsequently supported larger numbers of both populations. Through the 1990s, lynx populations increased and population estimates suggest >1,000 adult lynx likely occupy northern and western Maine spruce/fir flats.

Management History

- In 1967, the bounty on lynx ended and the hunting and trapping season for lynx was closed.

- In 1997, lynx were designated a species of special concern because information was not sufficient to determine if lynx qualified as threatened or endangered species under Maine's Endangered Species Act.

- In 1999, MDIFW and the USFWS started a 12-year telemetry study of lynx in northern Maine.

- In 2000, lynx were Federally listed as threatened in Maine and 13 other states due to inadequate habitat protections on federal lands in the western United States. At that time, lynx in Maine were just starting to make their comeback and based on historic accounts, the northeast was not considered an important area to the long-term persistence of lynx in the lower 48.

- In 2005, USFWS drafted an Interim Recovery Plan Outline for lynx.

- In 2006, lynx did not meet state listing criteria in Maine (exceed 500 adults), but remained a species of special concern.

- In 2008, MDIFW applied for an Incidental Take Permit for the accidental capture of lynx in traps set for other legal furbearing animals. In 2011, the USFWS developed an Environmental Assessment of our permit application.

- In 2009, the USFWS designated 6.4 million acres of Critical Habitat for lynx in northern Maine as required by the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

- In 2012, MDIFW completed a lynx species assessment (PDF) that documents the status of lynx in Maine to help guide conservation goals and management.

- In 2014, USFWS issued an Incidental Take Permit to MDIFW.

- In 2017, the USFWS reviewed the status of lynx in the lower 48 and recommended lynx no longer needed federal protection. Before the USFWS could move forward with removing the threatened species protections, they were sued. The lawsuit challenged the USFWS decision to delist lynx without a recovery plan. In a settlement agreement in federal court, the USFWS suspended delisting and agreed to finalize a recovery plan by December 2024.

- In 2024, the USFWS released the Recovery Plan for the Contiguous United States Distinct Population Segment of Canada Lynx. The plan summarizes the criteria and actions necessary to conserve lynx and achieve recovery of the species in the lower 48 based on the best available information.

Incidental Take

Photo Credit: Dorothy Fescke

When a species is listed as Threatened, it is protected from take. Take is defined as: to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct. Anyone whose otherwise-lawful activities will result in the "incidental take" of a listed wildlife species needs a permit. The permit allows the permit-holder to legally proceed with an activity that would otherwise result in the unlawful take of a listed species. Although lynx have been protected from harvest since 1967 in Maine, lynx are sometimes caught in traps set for furbearers during the regulated trapping season. Although most are released alive from these traps, the capture is considered a take under federal law. In 2014, the Department was issued an incidental take permit to allow otherwise lawful trapping of furbearers to continue if certain measures were in place to minimize the potential capture, serious injury, or mortality of lynx. Over the 15-year permit period (2014-2029), all licensed trappers and ADC agents are protected from take if the capture, injury, or death occurs in a legally set trap.

Research – MDIFW and USFWS 12-year Lynx Telemetry Study

Between 1999 and 2011, the USFWS and MDIFW conducted a study of radio-collared lynx on a 400 sq. km. area in northern Maine to estimate the abundance of lynx in Maine, their ability to survive and reproduce, and the factors that may limit their numbers. At the time, little was known about lynx in the northeastern United States, but Maine had the most consistent evidence of lynx presence. A year after this study was initiated, lynx were federally listed as a threatened species in Maine and 13 other States. The data from this study has been instrumental in the development of conservation planning to ensure the persistence of lynx in Maine.

Biologists captured, equipped, and monitored 85 lynx (44 males, 41 females) with radio collars and documented the birth of 111 kittens in 42 litters. Like elsewhere, predation and starvation were the leading cause of lynx mortalities and starvation losses appear to be related to a parasite that infects the lungs making it difficult for lynx to chase and capture prey. Lynx were often found in regenerating dense stands of spruce/fir saplings where hares were most common. Lynx raised their kittens in dense forests that contained blown down trees or brush piles for den structures. Lynx reproductive success was influenced by the abundance of their prey. When snowshoe hare were common (between 1999 and 2005), most female lynx had kittens. Conversely, when snowshoe hare were less common in Maine's regenerating spruce/fir clearcuts (2006- 2011), fewer lynx produced litters in 2007 to 2009. Although hare densities in regenerating clear cuts remained low in 2010, hare numbers increased in other stand types and all 5 radio collared female lynx gave birth to kittens. Throughout this study, lynx occupied relatively small areas and continued to use regenerating spruce/fir clearcuts. Habitat estimates from the Maine Forest Service and data from this study analyzed by IFW, USFWS, and the University of Maine were used to develop population estimates and habitat models to inform management planning efforts for lynx in Maine.

This study was funded by IFW, USFWS, Defenders of Wildlife, Forest Products Council, Kendall Foundation, Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund, National Council of Air and Stream Improvement, Plum Creek Timberlands, Sweet Water Trust, USGS-Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, University of Maine's Cooperative Forestry Research Unit and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Virtual lynx den site visit or on YouTube

Monitoring

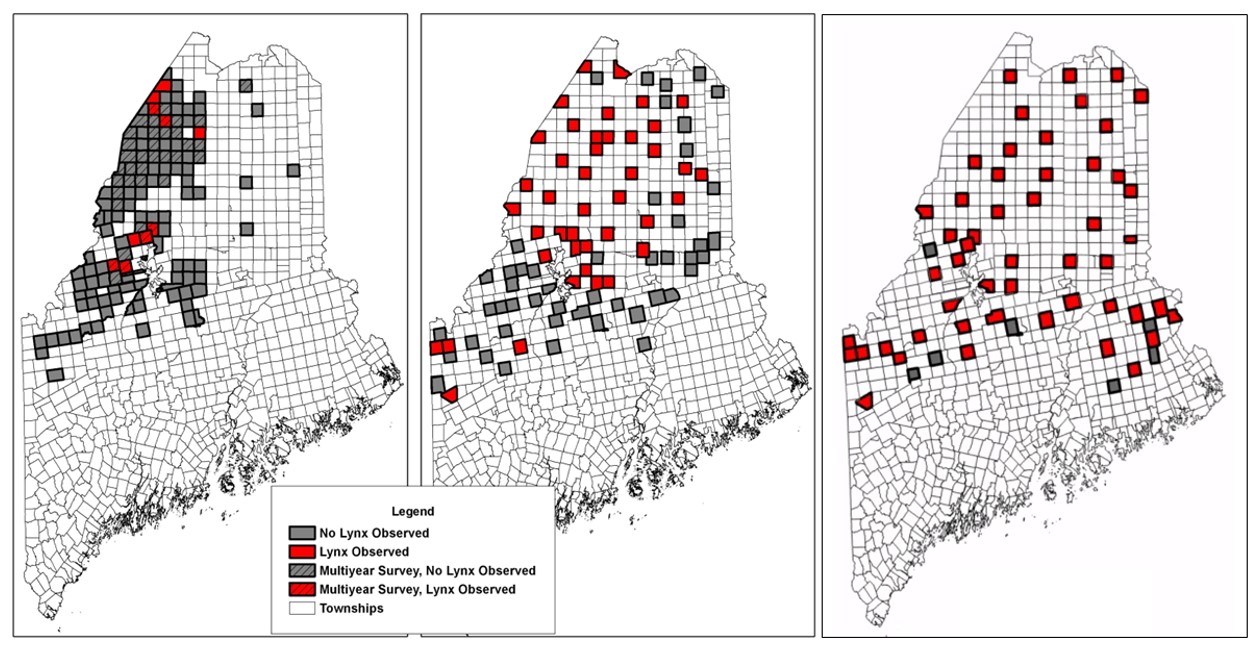

Between 1995 and 1999, the Department initiated winter track surveys to document the status of lynx and other rare carnivores along the border of Maine and Quebec. Although most towns were only surveyed once during a single winter, lynx tracks were observed in several locations (see red polygons in Figure). Track surveys conducted between 1995 and 1998 were stratified based on the acres of young forest. We found lynx in 29% of the survey areas with >2,000 acres of young forest and found lynx in 18% of the towns with <2,000 acres of young forest. In 2003, the Department initiated more extensive snow-track surveys to document lynx distribution statewide as part of a Maine Natural Areas Program/MDIFW survey effort to document rare species and communities in Maine (i.e., ecoregional surveys; Vashon et al. 2003, 2007, and 2010). Although surveys were conducted only once each winter, lynx were found in many more northern locations. We stratified surveys conducted between 2003 and 2008 by the probability of lynx occurrence (low vs. moderate/high) from an early habitat model (Hoving 2001) and observed lynx tracks in 44% of the surveyed townships. Track surveys were repeated from 2015-2019 using similar methods from the previous survey period (2003-2008). The results indicate a growing lynx population since the mid-1990s, with biologists finding lynx tracks in 51 townships (87% of those surveyed from 2015-2019; Dri et al. 2022).

Comparison of Maine townships that had lynx (red polygons) or no lynx (gray polygons) detected during snow track surveys in the 1994-1999 (left), 2003-2008 (center), and 2015-2019 (right) survey periods.

How to Prevent or Resolve Conflicts with Lynx

Although it is uncommon, conflicts sometimes arise when lynx pursue domestic animals. There are many ways to protect livestock and pets from predators. In many instances, removing or securing attractants and keeping small pets leashed and inside at night will address conflicts. Learn more about standard steps to avoid conflicts and fencing options.