Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Invertebrates → Rare Butterflies

Rare Butterflies

Hessel’s Hairstreak, Purple Lesser Fritillary, and Crowberry Blue are just some of Maine’s rarest butterflies that are both colorful in name and on the wing. In an effort to improve our knowledge of these and other priority butterflies, MDIFW is actively studying the group during statewide regional surveys. Attractive, conspicuous, and ecologically important, butterflies have garnered increasing attention from scientists and the general public as sentinels of habitat change. By documenting the distribution and status of the state’s butterfly fauna, MDIFW hopes to improve its understanding of the group and prioritize conservation efforts towards those species most vulnerable to decline and potential state extinction.

Through directed surveys and research, MDIFW has learned a great deal about Maine’s butterfly fauna in recent years, adding over a dozen previously undocumented species to the State list, which now stands at 121 species. Of special note is the relatively high proportion (~20%) of Maine butterflies that are extirpated (5 species) or state-listed as Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern (19 species), a pattern consistent with global trends elsewhere for the group.

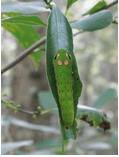

Spicebush Swallowtail larvae,

photo by Phillip deMaynadier

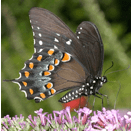

Spicebush Swallowtail adult,

photo by Tom Murray

Clayton's Copper,

photo by Corrine Michaud

The story of the Spicebush Swallowtail is a hopeful one that illustrates the benefit of dedicated survey effort combined with natural history detective work. Until recently, this butterfly was thought to be extirpated (extinct in Maine) ? a dubious status that MDIFW works hard to avoid for any native wildlife. Unfortunately, with only a single previous published observation dating from 1934, the Spicebush Swallowtail seemed destined to join the ranks of Maine’s other lost butterflies. In an effort to confirm the status of this mysterious insect, MDIFW recently embarked on targeted surveys. Most butterflies are restricted as caterpillars to foraging on specific plant species, which in the case of the Spicebush Swallowtail includes only two plants, both also rare in Maine: Sassafras and Spicebush. To increase the chance of success, survey efforts were directed solely at the few remaining rich hardwood forests in York and Cumberland Counties containing healthy populations of the host plants. Patience and planning were rewarded when several occupied swallowtail caterpillar nests were discovered in two swamps in Berwick and Wells, providing the first evidence of breeding for this rare butterfly in Maine. Significant in its own right, the Spicebush Swallowtail is also a faunal indicator of the integrity of enriched, mesic hardwood forests ? a natural community that is increasingly threatened in the rapidly developing landscape of southern Maine. With only a small number of forest patches remaining that can possibly host additional Spicebush Swallowtail populations, mostly on unprotected land, MDIFW will make it a priority to conduct further surveys. The Spicebush Swallowtail may be considered as a candidate for future state Endangered or Threatened listing status.

Another rare butterfly that MDIFW has learned a great deal about in recent years is the Clayton’s Copper. Listed as Endangered in Maine, this butterfly is known from just 9-10 sites in northern and eastern regions of the state. It is found only in association with its larval host plant, the shrubby cinquefoil, which also serves as the primary nectar plant for adults. This uncommon shrub rarely occurs in stands large enough to support viable populations of the butterfly and grows best in circumneutral fens (peatlands rich in calcium carbonate or limestone) - a rare habitat type in Maine.

Since 2006, MDIFW has partnered with researchers and graduate students at the University of Maine to investigate key life history, habitat and conservation questions about Clayton’s Copper. We now have estimates for population size, flight period, and cinquefoil patch size at each colony, as well as a better understanding of the conservation importance of each site. The University is also looking at the genetic relationship between the distinct population clusters of Clayton’s Copper. This research will help shed light on if and how the butterflies move between sites and whether each subpopulation has the ability to persist over time. Another study is focused on identifying environmental characteristics of the wetlands where Clayton’s Copper is found and on specific qualities of the host plant, which might explain why the butterfly occurs at some cinquefoil stands but not others.

To learn more about Maine’s rare butterflies contact MDIFW to receive an updated checklist of the butterflies of Maine, or visit the list of state-listed Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern invertebrates.

This work is supported by volunteer contributions, the State Wildlife Grants program (USFWS), University of Maine, The Nature Conservancy, and state revenues from the Loon License Plate, Chickadee Check-off and Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund.