Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Birds → Shorebirds

Shorebirds

Migratory Shorebird Use of the Maine Coast

Semipalmated Sandpiper

Photo Credit: John Gavin, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology

This report summarizes information on shorebird use of the Maine coast. See also Issue Profile: Docks and Piers in Shorebird Feeding and Roosting Areas for a discussion of issues associated with placement of docks and piers in shorebird feeding and roosting areas identified as Significant Wildlife Habitat under Maine’s Natural Resources Protection Act (38 M.R.S.A.).

What is a shorebird?

Shorebirds are a diverse group of birds that include sandpipers, plovers, turnstones, knots, curlews, dowitchers, and phalaropes. This group does not include herons, gulls, or cormorants.

North America has the greatest diversity of shorebird species and largest numbers of shorebirds in the world. Thirty-eight shorebird species spend some portion of their annual life cycle in Maine.

Shorebirds are an important group for management consideration, because large numbers of these birds concentrate in discrete areas of coastal habitat where they are highly susceptible to disturbance, development, and environmental contaminants.

What is the status of shorebirds in Maine?

Analyses of the International Shorebird Survey, Maritime Shorebird Survey, Arctic Shorebird Breeding Survey, and Breeding Bird Survey all suggest several shorebird species are experiencing significant downward population trends.

More than 20 species of shorebirds depend on Maine coastal habitats to feed and rest during migration from the high arctic breeding grounds of Canada to the furthest tip of South America. The more common migratory shorebirds found in Maine include:

- Black-bellied Plover

- Semipalmated Sandpiper

- Least Sandpiper

- Short-billed Dowitcher

- Ruddy Turnstone

- Red Knot

- Dunlin

- Spotted Sandpiper

The Maritimes researchers looked at 16 species of shorebirds and discovered 13 experienced consistent declines between 1970 and 2000. Studies in the Upper Bay of Fundy found Black-bellied Plovers were down 46% in the 1980s and 33% in the 1990s; they attributed these dramatic declines to baitworm harvesting.

Ruddy Turnstone

Photo Credit: Jonathan Mays

Photo Credit: Rich Bard

In addition to population declines, recent studies of staging shorebirds in the Bay of Fundy are also finding shorebirds are spending longer periods at staging areas to acquire the fat reserves they need [in the 1970s the average length of stay was 10 days compared with 15-20 days in the 1990s].

Maine supported 300,000 to 500,000 Semipalmated Sandpipers and tens of thousands of other species in the 1970s. Today, we are observing much lower numbers, though some shorebird populations remain stable.

Causes of shorebird population declines are difficult to determine due to their extensive migrations and potential to be affected at many different stages of their annual cycle. Once a species is listed Endangered or Threatened, it is very expensive to maintain and/or improve their numbers. For example, population monitoring and management efforts to maintain current levels of Piping Plovers on Maine’s beaches cost over $75,000 annually even with assistance from volunteers; without volunteer effort the cost can easily exceed $150,000.

Do any shorebirds nest in Maine?

Eight shorebird species nest in Maine:

- Piping Plover (Federally Threatened, State Endangered)

- Upland Sandpiper (State Threatened)

- Spotted Sandpiper

- Killdeer

- American Woodcock

- Common Snipe

- American Oystercatcher (State Special Concern)

- Willet.

Of the eight species of nesting shorebirds, only the Piping Plover and Upland Sandpiper are species requiring protective measures. Piping Plover nesting and foraging habitats are mapped and designated as Essential Habitat under the Maine Endangered Species Act and Significant Wildlife Habitat under the Natural Resources Protection Act. Upland Sandpipers are a grassland bird requiring different management criteria and strategies yet to be developed by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Priority 1 Nesting Species Identified in Maine’s Wildlife Action Plan:

- Piping Plover

- Upland Sandpiper

Priority 2 Nesting Species Identified in Maine’s Wildlife Action Plan:

- Willet

Priority 3 Nesting Species Identified in Maine’s Wildlife Action Plan:

- American Oystercatcher

What kinds of habitats do shorebirds need?

Habitats used by migrating shorebirds range from intertidal mudflats to sandy beaches and rocky intertidal areas. Migrating shorebirds need feeding areas with high concentrations of intertidal invertebrates and roosting areas, such as sand/gravel bars, rock islands and ledges, and saltmarsh pannes that remain above the high water mark during high tide, thus allowing the birds to rest and preen when feeding areas are unavailable. These habitats, used only during migration, are called “staging areas”. Staging areas provide migrating shorebirds with the food resources required to acquire the large fat reserves necessary to fuel their transoceanic migration to wintering areas.

Habitats used by migrating shorebirds range from intertidal mudflats to sandy beaches and rocky intertidal areas. Migrating shorebirds need feeding areas with high concentrations of intertidal invertebrates and roosting areas, such as sand/gravel bars, rock islands and ledges, and saltmarsh pannes that remain above the high water mark during high tide, thus allowing the birds to rest and preen when feeding areas are unavailable. These habitats, used only during migration, are called “staging areas”. Staging areas provide migrating shorebirds with the food resources required to acquire the large fat reserves necessary to fuel their transoceanic migration to wintering areas.

Why is Maine so important to shorebirds?

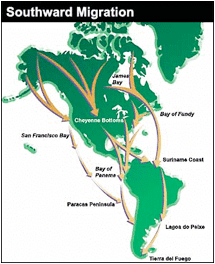

Many shorebirds are capable of flying great distances, making migratory journeys from the high arctic breeding grounds of Canada to the furthest tip of South America. Though they stop at specific staging areas to refuel along their migratory routes, most shorebirds are capable of flying 1,200 to 3,000 mile segments of their journey nonstop.

The greatest numbers of shorebirds feed and roost along the Maine coast during their southward migration. Migration begins in July and continues through November; most species arrive between July 15 and September 15.

For most shorebird species, the adults and juveniles migrate from the breeding grounds at different times. Adults generally leave before juveniles are capable of sustained flight and arrive at Maine staging areas starting in July and peaking in early August. The females of several species migrate first, followed 2-3 weeks later by the males. Juveniles arrive in mid August through September. One species (Dunlin) migrates later, arriving in Maine in October and November.

Shorebirds feed on intertidal invertebrates found on mudflats and saltmarsh pannes and generally stay only 10-20 days at coastal staging areas. In that short period, birds must double their body weight to acquire the fat reserves needed to fuel a nonstop, transoceanic flight to coastal and inland habitats in the Bahamas, Florida, and South America (2,000 miles or more). Once over the ocean, they are committed to the migration; if birds do not have the reserves to reach South America, they plummet into the sea or may reach their wintering areas in such poor condition that they die shortly after arriving.

Feeding and roosting areas associated with staging areas occur along the entire Maine coast. Downeast Maine (Trenton Bay east to Perry) is probably the most important fall migratory stopover area in the eastern U.S. for Semipalmated Sandpipers, Semipalmated Plovers, Black-bellied Plovers, Ruddy Turnstones and Short-billed Dowitchers (Famous and Ferris 1980). McCollough and May (1980) reported over 150,000 shorebirds feeding and roosting in Cobscook Bay between July and September 1979.

The relatively few shorebirds (namely Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs and Black-bellied Plovers) that migrate through Maine during their northward migration [April - June] primarily use staging areas in Kittery, Wells, and Biddeford, and along the coast to Phippsburg, Georgetown, and Boothbay Harbor.

Maine staging areas provide many shorebirds with the reserves to accomplish the biggest migration challenge in their annual life cycle. Whether or not shorebirds are successful in completing their long journey is largely dependent on the quantity and quality of feeding habitats and maintaining a finite number of roosting habitats along the Maine coast.

Sandpipers banded in Eastport in 1980 were observed 48 hours later in Suriname, South America. Larger shorebirds equipped with satellite radios have been documented flying nonstop for 9 days to reach their next staging area.

Some species winter in the northern part of South America; others refuel and continue flying nonstop to Argentina and Chile. The spectacular migrations of shorebirds are one of the greatest biological wonders of the world.

Since shorebirds traverse the entire western hemisphere, where does Maine fit in?

There are few locations along the southward migration path that provide adequate food resources in conjunction with nearby suitable roosting sites at the appropriate time to meet energy requirements. Therefore, shorebirds often concentrate in extremely large groups at distantly separated wetlands. Coastal staging areas in the Gulf of Maine are recognized as the most important southward staging area for shorebirds in eastern North America.

What Species Comprise Maine’s Staging Shorebirds?

Twenty-three species regularly migrate through Maine of which:

Federally listed as Threatened: Red Knot

State listed as Special Concern:

- Red-necked Phalarope

- Whimbrel

- Red Knot

- Semipalmated Sandpiper

- Lesser Yellowlegs

Priority 1 SGCN Staging/Wintering Species Identified in Maine’s State Wildlife Action Plan:

- Red Knot

- Lesser Yellowlegs

- Purple Sandpiper (wintering species)

Priority 2 SGCN Staging Species Identified in Maine’s State Wildlife Action Plan:

- Whimbrel

- Ruddy Turnstone

- Sanderling

- Semipalmated Sandpiper

- Red-necked Phalarope

- Solitary Sandpiper

The two most critical factors in determining shorebird distribution are feeding areas with high densities of invertebrates and suitable roosting areas in close proximity to feeding areas for sleeping and preening. Shorebirds need both feeding and roosting areas [there are few locations along the southward migration path that provide adequate food resources] in conjunction with nearby suitable roosting sites at the appropriate time to meet energy requirements.

Banding studies and recent telemetry studies conducted in Maine indicate that shorebirds exhibit extreme fidelity to traditional staging areas (MDIFW unpublished data). If habitats are degraded from development, pollution, or disturbance, birds do not readily relocate to new areas. If traditional staging areas are not adequately protected and become unsuitable, these transoceanic migrants cannot obtain the energy reserves needed to complete their migration to the wintering grounds and survive to the following breeding season.

Shorebird Feeding Areas

Photo Credit: Lindsay Tudor

Shorebirds feed along the water line, as mudflats are gradually exposed with the retreating tide. Just after high tide, shorebirds concentrate very close to the upland edge on the first mud showing, and shorebirds will return to the same areas, which are the last mud available as the tide comes in. Shorebirds need to feed throughout the low tide cycle; therefore, the first and last mud available is critical to gaining the fat reserves they need. Shorebird feeding areas must have high densities of invertebrates, low disturbance, and be free of contaminants.

Shorebird Roosting Areas

Shorebird roosts are often sandy beaches, sand/gravel bars, rock ledges, or islands with little or no vegetation. Roosting areas provide migrating shorebirds with areas to rest and preen during high tide when feeding areas are inundated, thus reducing energy costs and maintaining a positive energy flow. Saltmarsh habitat often provides ditches, pools, and pannes where shorebirds can feed and rest throughout the tidal cycle.

Shorebird roosting areas must be located above the high water mark and be free of disturbance. Ideally, shorebird roosts are located in close proximity to feeding areas.

Shorebird Significant Wildlife Habitat [SWH]

Shorebird nesting, feeding, and staging areas and a zone surrounding those areas, are significant wildlife habitats. The zone surrounding a shorebird feeding area is 100 feet wide, and is referred to as the “feeding buffer”. The zone surrounding a shorebird roosting area is 250 feet wide and is referred to as “the roosting buffer” under the Natural Resources Protection Act (38 M.R.S.A.).

The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife [MDIFW] has documented over 700 areas where shorebirds feed and roost during migration through Maine, however only 81 roosts and 100 feeding areas have met our criteria as Significant Wildlife Habitat [SWH] for migrating shorebirds coast wide. These areas are exceptional habitats and are critical for the well-being of eastern North American shorebirds.

What are the threats to shorebird feeding and roosting areas?

Shoreline development and associated human related disturbances

Human disturbance of migrant birds is a conservation issue of international importance. Increased human development of coastal landscapes for homes, recreation, and commercial ventures has reduced the available foraging habitat of coastal birds. Problems caused by people include increased predator access, increased number and diversity of predators [including domestic dogs and cats], increased human disturbance, and problems with environmental contaminants.

Studies have revealed that shorebirds are more affected by the presence of humans than any other group of waterbird. People within 300 feet of feeding shorebirds are a significant contributor to decreases in foraging time. Studies recommend buffering direct visual contact between birds and disturbances and buffering for increased noise levels. It follows that structures and associated noise and lights within 300 feet can be disruptive to feeding and roosting shorebirds.

Migrant shorebirds have a limited period of time at a staging area and limited foraging space; therefore, time spent avoiding a disturbance is less time spent foraging or resting, which can interfere with needed weight gain.

Docks and marinas

There are several problems with docks: shading, erosion, leaching/spilling of chemicals, alteration of habitat, and human disturbance. Shorebirds will not forage under or near such structures. Accumulation of docks in a cove will render the cove no longer functional for feeding shorebirds due to associated disturbances and habitat alterations. Shorebirds need to feed throughout the entire low tide cycle; shoreline docks prohibit their feeding on the first and last mud available on either side of the high tide.

Contaminants

Because shorebirds have high metabolic rates and require rapid cycles of weight gain, they are very susceptible to contaminants. Certain contaminants can interfere with their metabolism and navigational abilities.

Sewage outfalls and river discharge

Sewage outfalls and river discharge can cause organic enrichment, freshwater flush, and sedimentation, resulting in diminished invertebrate concentrations.

Oil Spills

Not only are shorebirds impacted from direct contact with oil, but oil spills can decimate the invertebrate food base for years after the spill.

Predators

Many predators such as raccoons, foxes, dogs, and cats are associated with increased coastal development.

Intertidal mussel dragging

Intertidal mussel dragging causes severe and lasting damage to marine invertebrates.

Clam and baitworm harvesting

Clam and baitworm harvesting 1) decreases the number of sand worms, blood worms, and other invertebrates available for shorebirds, and 2) collapses and destroys invertebrate burrows making it more difficult for shorebirds to locate invertebrates.

Why don’t shorebirds get used to people?

There isn’t time. Although many species, like gulls, are able to habituate over time to human presence and even take advantage of it, shorebirds coming from the arctic are only on a staging area for 10 - 20 days and do not have the time to acclimate to people and their activities. Shorebird species have different tolerances to disturbance. Black-bellied Plovers and Piping Plovers are very susceptible to impacts from disturbance, whereas Semipalmated Sandpipers and Sanderlings are a little more tolerant of human activities. All shorebirds are negativelyimpacted by humans and/or pets moving quickly within 300 feet of the birds.

Conclusion

Surveys suggest the majority of shorebird species staging on the east coast are suffering significant downward trends. In addition to population declines, recent studies of staging shorebirds in the Bay of Fundy are also finding shorebirds are spending longer periods at staging areas to acquire the fat reserves they need [in the 1970s the average length of stay was 10 days compared with 15-20 days in the 1990s].

Causes of shorebird population declines are difficult to determine due to their extensive migrations and potential to be affected at many different stages of their annual cycle. Once a species is listed Endangered or Threatened it is very expensive to maintain and/or improve their numbers. For example, population monitoring and management efforts to maintain current levels of Piping Plovers on Maine’s beaches cost over $75,000 annually even with assistance from volunteers; without volunteer effort the cost can easily exceed $150,000.

In Maine, shorebirds are affected by many different threats. Conservation requires minimizing cumulative impacts. The Significant Wildlife Habitat provision under Maine’s Natural Resources Protection Act [38 M.R.S.A.] allows MDIFW to implement protective measures to avoid and minimize many of the threats shorebirds face in Maine, increasing their chances for a successful migration and return to Maine the following year.

Literature cited:

Famous, N. C. and C. Ferris. 1980. Waterbirds. In An ecological characterization of coastal Maine, ed. S. I. Fefer and P.A. Schettig. USFWS, Ma pp. 14-1 - 14-54

McCollough, M. A. and T. A. May. 1980. Habitat utilization by southward migrating shorebirds in Cobscook Bay, Maine during 1979. Proj. rep. Univ. Maine, Orono, Maine