June 20, 2022 at 9:32 pm

Question: What’s blue and white and frequents the Deer Isle coastline?

Answer: A Mariner

But, not just any Mariner…there are the Mariners who work on ships, the Mariners who are the students of Deer Isle-Stonington High and Elementary Schools, and there is now a great blue heron named Mariner!

Meet “Mariner,” the newly GPS-tagged great blue heron from Deer Isle. On June 3rd, Mariner became the 11th great blue heron in Maine to be added to the Heron Tracking Project that began in 2016. She is also the first heron tagged in the Downeast area, an area that once hosted hundreds of nesting pairs of herons on its coastal islands, whereas now we think there are less than 50 pairs amongst these same islands.

Over the past six years, we tagged herons in Orrington, Orono, Palmyra, Gray, Easton, and Harpswell. We chose to work in Deer Isle this year for several reasons – close ties with a few local volunteers, an active and supportive land trust (Island Heritage Trust), and a connection with two retired biologists, one of which had written a book about heron migration!

Back in September 2020, I opened an email with the subject line, “Heron book.” The sender was author Marnie Crowell, a retired biologist living in Deer Isle, who had published a book in 1980 (Great Blue: the Odyssey of a Great Blue Heron, Times Books) about following the fall heron migration from an island in Stonington, Maine, to Trinidad. I was immediately intrigued, ordered the book on ebay, read it in one fell swoop, then spoke with Marnie over the phone. Her first-hand account of heron migration as she herself traveled to Bermuda, the West Indies, and Trinidad so closely mirrored what we were seeing with our tagged herons like Harper. It sounded as if what we were learning from Harper’s impressive migration to Cuba via cutting edge technology supported observations documented as far back as the 1980s when bird banding was the best form of tracking technology. When deciding where to target a heron for tagging this year, the Deer Isle-Stonington area seemed like a must!

Marnie connected me to Martha Bell of the Island Heritage Trust, who in turn, connected me with two groups of students who were willing to help with the field work: a high school science class, and the elementary school’s after school program called, Mariners Soar (are you seeing where Mariner came from?). Each group took one day of the week to collect baitfish from our minnow traps and release them into our bait bins, creating enticing dinner plates for local great blue herons. Volunteers and staff baited the bins the other five days of the week. For one month, we worked collaboratively to find freshwater sites where herons forage and to stock bait bins with baitfish at each of these sites. Within a few weeks we had a heron on camera feeding from a bait bin and we knew we were ready to set out for trapping and tagging.

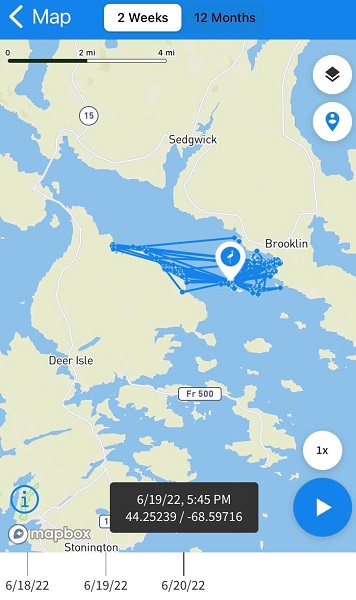

The morning of June 3rd was very foggy. We set our traps well before sunrise and sat in vehicles as blinds in the nearby driveway. Within less than an hour and before the fog had completely lifted, we had our heron. Over the next hour we measured the bird’s mass, beak, legs, and wings, took a blood sample for sexing, and attached a leg band and a solar-powered GPS transmitter using a Teflon ribbon backpack. This transmitter records the bird’s location up to every 5 minutes and relays that information to a website via a cell tower connection. This enables anyone to track the bird’s movements whether it is in Deer Isle, elsewhere in Maine, the U.S., or a distant country. The transmitter also measures the bird’s speed, altitude, and direction.

I recently met with the after school group to name the heron. Very fittingly, we agreed upon “Mariner,” the schools’ mascot, and a resemblance of this heron’s lifestyle. In the past three weeks we have learned she is likely nesting on an island in Eggemoggin Reach and frequents the intertidal shore for foraging. The island where she nests was not known as a heron nesting island before Mariner’s tagging, so we’ve already learned extremely valuable information from her.

We are excited to witness Mariner’s travels, learn about her habits and her favorite habitats, and discover how far and wide she chooses to go when she leaves Maine. Her odyssey will be her own, but we look forward to comparing it to that which Marnie Crowell wrote about 40 years ago.

Anyone can follow Mariner’s travels on movebank.org or on your smartphone with the Animal Tracker app. Visit the following page for detailed instructions: mefishwildlife.com/trackherons.

This work could not have been accomplished without the help and support of many volunteers, teachers, and landowners, and the generous donation by Hope Hilton. This project is also funded in part by the USFWS Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program (WSFR), Maine Chickadee Check-Off, Maine Loon Conservation Registration Plate, and Maine Birder Band.