October 23, 2016 at 9:05 am

By Wildlife Biologist Danielle D'Auria

Did you ever wonder where Maine’s great blue herons go in the winter? You are about to find out! This spring, biologists from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW) tagged five adult great blue herons with GPS transmitters as part of an ongoing effort to better understand the state’s great blue heron population. The great blue heron tagged in Palmyra and named “Nokomis” just showed up in Haiti on October 20th, and anyone can watch to see if she remains there for the winter and if she returns to Palmyra in the spring. The transmitters that the herons are wearing as a backpack represent the cutting edge of telemetry technology and transmit GPS locations via the cell phone network to an open source website (www.movebank.org). By following a few simple instructions, anyone with a computer or smartphone can go online and view the birds’ movements on an interactive map on the internet or through a free App called Animal Tracker. Users can also download all or portions of the data to view in Google Earth, Excel, or ArcGIS.

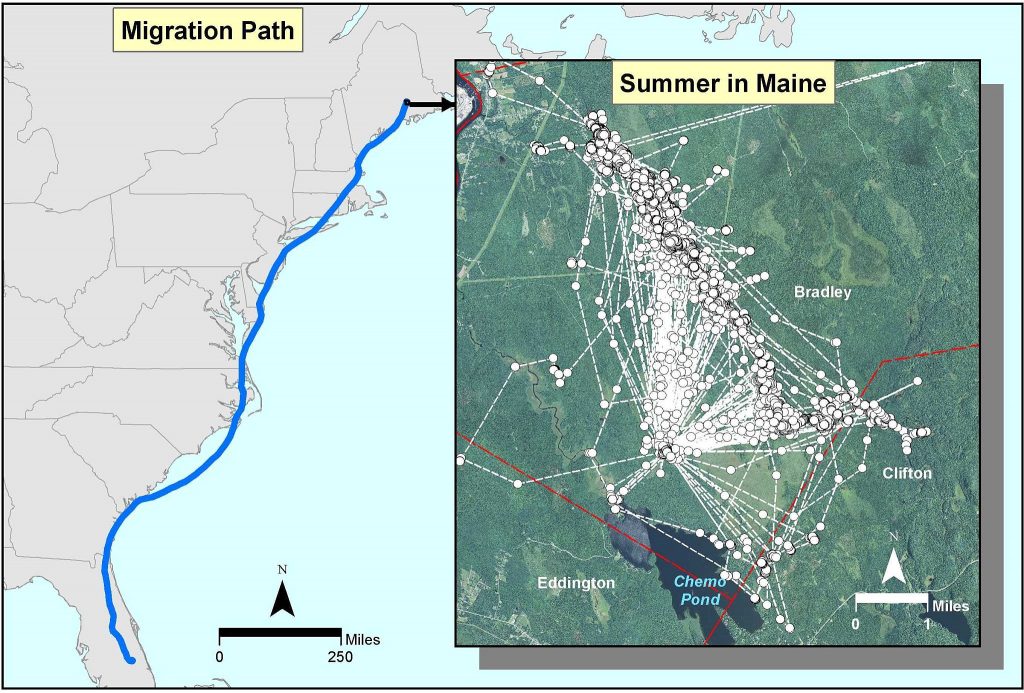

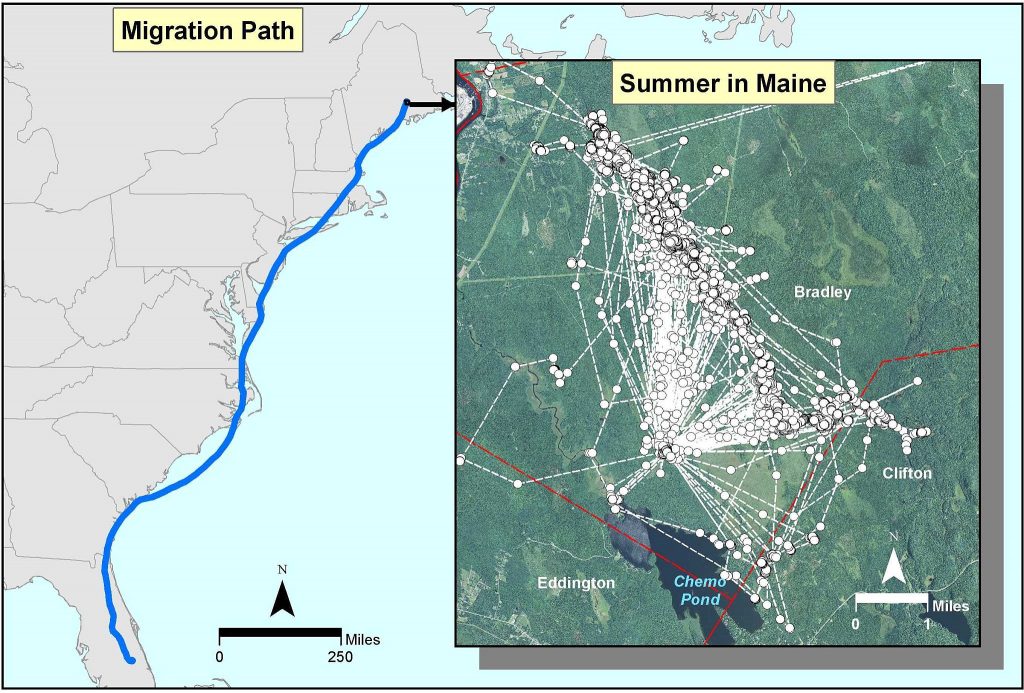

After watching the birds move amongst local wetlands for four months, we observed the southward migration of “Sedgey” to Florida during Tropical Storm Hermine. He first stopped in Massachusetts before doing a 29-hr nonstop flight to southern Georgia. He then more leisurely made his way to an agricultural area just north of Lake Okeechobee in Florida, where he has been since September 6th.

[caption id="attachment_1988" align="alignleft" width="225"] “Cornelia,” with her backpack transmitter, takes a few steps before flying off. Photo by Joyce Love.[/caption]

A few weeks later on September 23rd, Cornelia embarked on her journey to North Carolina. She did not do a marathon flight like Sedgey, and instead stopped every few hours to spend 3-7 hours in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. She then went on to Virginia, which was where we initially thought she might settle for the winter, but after a few days she moved again, this time into North Carolina.

The transmitters were purchased with a grant from the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund. They are solar-powered and are expected to provide years of data for each tagged heron. The herons were tagged in June with the help of students and teachers from several schools across the state. The students and teachers set and checked minnow traps, identified and measured the baitfish caught, and placed the baitfish into a bait bin in order to get a great blue heron to regularly feed from it. They also used game cameras to photograph the bait bins when the students were not there themselves. After a heron became accustomed to feeding from the bait bin, MDIFW and researchers Dr. John Brzorad (Lenoir-Rhyne University) and Dr. Alan Maccarone (Friends University) set out an array of modified foothold traps near the bait bin to capture the heron so they could tag it with a GPS transmitter. The use of modified foothold traps has been perfected by Brzorad, and involves watching the set traps from a blind until a heron steps into one of the traps. Once trapped, it is then quickly retrieved by the researchers for processing. The bird is kept calm with a hood over its eyes while researchers take measurements and a blood sample to determine the sex of the bird, and attach the transmitter.

Drs. Brzorad and Maccarone have been using these same transmitters since 2013 and have paired nearly 20 birds (great egrets and great blue herons) with school systems in five other states. In Maine, five great blue herons were trapped and tagged in Orrington (2 birds), New Gloucester, Orono, and Palmyra:

“Cornelia,” with her backpack transmitter, takes a few steps before flying off. Photo by Joyce Love.[/caption]

A few weeks later on September 23rd, Cornelia embarked on her journey to North Carolina. She did not do a marathon flight like Sedgey, and instead stopped every few hours to spend 3-7 hours in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. She then went on to Virginia, which was where we initially thought she might settle for the winter, but after a few days she moved again, this time into North Carolina.

The transmitters were purchased with a grant from the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund. They are solar-powered and are expected to provide years of data for each tagged heron. The herons were tagged in June with the help of students and teachers from several schools across the state. The students and teachers set and checked minnow traps, identified and measured the baitfish caught, and placed the baitfish into a bait bin in order to get a great blue heron to regularly feed from it. They also used game cameras to photograph the bait bins when the students were not there themselves. After a heron became accustomed to feeding from the bait bin, MDIFW and researchers Dr. John Brzorad (Lenoir-Rhyne University) and Dr. Alan Maccarone (Friends University) set out an array of modified foothold traps near the bait bin to capture the heron so they could tag it with a GPS transmitter. The use of modified foothold traps has been perfected by Brzorad, and involves watching the set traps from a blind until a heron steps into one of the traps. Once trapped, it is then quickly retrieved by the researchers for processing. The bird is kept calm with a hood over its eyes while researchers take measurements and a blood sample to determine the sex of the bird, and attach the transmitter.

Drs. Brzorad and Maccarone have been using these same transmitters since 2013 and have paired nearly 20 birds (great egrets and great blue herons) with school systems in five other states. In Maine, five great blue herons were trapped and tagged in Orrington (2 birds), New Gloucester, Orono, and Palmyra:

Map showing the migration path of “Sedgey,” and where he spent his summer in Maine. White dots and lines are locations and movements between points.[/caption]

Map showing the migration path of “Sedgey,” and where he spent his summer in Maine. White dots and lines are locations and movements between points.[/caption]

“Cornelia,” with her backpack transmitter, takes a few steps before flying off. Photo by Joyce Love.[/caption]

A few weeks later on September 23rd, Cornelia embarked on her journey to North Carolina. She did not do a marathon flight like Sedgey, and instead stopped every few hours to spend 3-7 hours in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. She then went on to Virginia, which was where we initially thought she might settle for the winter, but after a few days she moved again, this time into North Carolina.

The transmitters were purchased with a grant from the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund. They are solar-powered and are expected to provide years of data for each tagged heron. The herons were tagged in June with the help of students and teachers from several schools across the state. The students and teachers set and checked minnow traps, identified and measured the baitfish caught, and placed the baitfish into a bait bin in order to get a great blue heron to regularly feed from it. They also used game cameras to photograph the bait bins when the students were not there themselves. After a heron became accustomed to feeding from the bait bin, MDIFW and researchers Dr. John Brzorad (Lenoir-Rhyne University) and Dr. Alan Maccarone (Friends University) set out an array of modified foothold traps near the bait bin to capture the heron so they could tag it with a GPS transmitter. The use of modified foothold traps has been perfected by Brzorad, and involves watching the set traps from a blind until a heron steps into one of the traps. Once trapped, it is then quickly retrieved by the researchers for processing. The bird is kept calm with a hood over its eyes while researchers take measurements and a blood sample to determine the sex of the bird, and attach the transmitter.

Drs. Brzorad and Maccarone have been using these same transmitters since 2013 and have paired nearly 20 birds (great egrets and great blue herons) with school systems in five other states. In Maine, five great blue herons were trapped and tagged in Orrington (2 birds), New Gloucester, Orono, and Palmyra:

“Cornelia,” with her backpack transmitter, takes a few steps before flying off. Photo by Joyce Love.[/caption]

A few weeks later on September 23rd, Cornelia embarked on her journey to North Carolina. She did not do a marathon flight like Sedgey, and instead stopped every few hours to spend 3-7 hours in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. She then went on to Virginia, which was where we initially thought she might settle for the winter, but after a few days she moved again, this time into North Carolina.

The transmitters were purchased with a grant from the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund. They are solar-powered and are expected to provide years of data for each tagged heron. The herons were tagged in June with the help of students and teachers from several schools across the state. The students and teachers set and checked minnow traps, identified and measured the baitfish caught, and placed the baitfish into a bait bin in order to get a great blue heron to regularly feed from it. They also used game cameras to photograph the bait bins when the students were not there themselves. After a heron became accustomed to feeding from the bait bin, MDIFW and researchers Dr. John Brzorad (Lenoir-Rhyne University) and Dr. Alan Maccarone (Friends University) set out an array of modified foothold traps near the bait bin to capture the heron so they could tag it with a GPS transmitter. The use of modified foothold traps has been perfected by Brzorad, and involves watching the set traps from a blind until a heron steps into one of the traps. Once trapped, it is then quickly retrieved by the researchers for processing. The bird is kept calm with a hood over its eyes while researchers take measurements and a blood sample to determine the sex of the bird, and attach the transmitter.

Drs. Brzorad and Maccarone have been using these same transmitters since 2013 and have paired nearly 20 birds (great egrets and great blue herons) with school systems in five other states. In Maine, five great blue herons were trapped and tagged in Orrington (2 birds), New Gloucester, Orono, and Palmyra:

- “Snark” is a male trapped in Orrington and adopted by Haworth Academic Center in Bangor. The students chose his name because they had recently read Lewis Carroll’s poem, “Hunting of the Snark.”

- “Sedgey” is a male trapped in Orrington and adopted by Center Drive School. “Sedgey” was named after the stream on which it was trapped: the Sedgeunkedunk.

- “Cornelia” is a female trapped at the New Gloucester Fish Hatchery, adopted by the Gray-New Gloucester High School. She had gotten into a fish rearing raceway at the hatchery, making her an easy capture with a long-handled net.

- “Mellow” is a female trapped at Pine Ponds on Orono Land Trust property and adopted by Old Town High School.

- “Nokomis” is a female trapped in Palmyra and adopted by Nokomis Regional High School in Newport.

Map showing the migration path of “Sedgey,” and where he spent his summer in Maine. White dots and lines are locations and movements between points.[/caption]

Map showing the migration path of “Sedgey,” and where he spent his summer in Maine. White dots and lines are locations and movements between points.[/caption]Categories