September 15, 2022 at 2:30 pm

Despite the recent warm temperatures, there are many signs that summer is winding down: shorter days and cooler nights, school bus traffic, and young great blue herons out on the landscape. Following the exciting yet dangerous time when young learn to fly, most great blue herons have completed nesting sometime in July or August. After their young have fledged, there usually isn’t a reason for the adults or young to return to the nest or colony until the next breeding season. In the meantime, they spread out on the landscape, focus on their favorite fishing spots, and bulk up in preparation for fall migration.

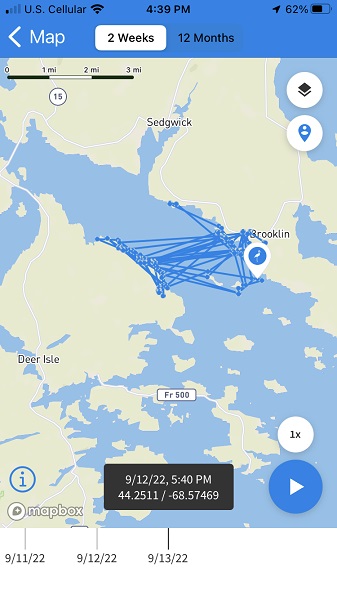

We have seen this pattern of behavior over and over with our GPS-tagged herons, and Mariner – newly tagged this past June – is no different. She nested on an island in Eggemoggin Reach. Mariner’s transmitter indicated she travelled back and forth repeatedly to a single spot for all of June and most of July. These trips are from her foraging sites up and down the coastline of the mainland, islands, and freshwater wetlands, to her nest where she then regurgitates food for her young. Upland colonies like hers can be difficult to observe without disturbing the birds. Due to the dense foliage of upland colonies, we must get very close to adequately see the nests and evidence of nesting behavior. To avoid disturbing Mariner during nesting, we chose to visit her colony well after her last visit on August 3rd.

Last week, myself and volunteers involved in tagging Mariner this past spring, set off for her nesting island to see what we could find. The first step was getting ferried to shore in “Hey Bub” from our main vessel, a 1961 Penbo Cruiser named, “Eider.”

Once on shore, we were quickly distracted by loafing shorebirds. We got out the spotting scope (I knew there was a reason I lugged it along) and saw about a dozen semipalmated plovers.

It was high tide, and we had to walk along the narrow shore until we could find an easy way to the interior of the island.

We trekked through low alders, goldenrod, and milkweed, and even saw a few monarch butterflies.

Staying the course towards the small forested area, eventually stick nests became visible high in the trees.

Every time a stick nest was spotted; we’d scour the ground for evidence it was active. We first found some feathers.

We found eggshells. Great blue heron eggs are similar in size to a chicken egg and a pale blue color. After the young hatch, the adults toss the shells over the edge of the nest to the ground. Presence of the white membrane detached from most of the shell indicates these eggs hatched. Sometimes we find eggshells without the membrane and with punctures that indicate they were predated.

We found bones from young great blue herons of varying sizes. These bones are the sternum and keel bones. There are three in this photo (note the smallest one to the left). Not all herons that hatch fledge successfully. Some may fall out of the nest, get pushed or attacked by siblings, or fall victim to predators.

We also found an osprey nest. They tend to be bigger and bulkier than a heron nest., and usually at the very top of the tree. The osprey nest is in the upper right at the top of the tree, hidden by the spruce branches. There were two additional nests below the osprey nest (only one is shown here) that we think are heron nests.

Our final count was 13 possible great blue heron nests. A few were small and possibly not used this past year. This thriving nesting location was unknown until Mariner “showed” it to us through her tracked movements. We don’t suspect the colony has been here more than a couple years.

Before the end of our adventure, we made sure to get a group photo, and vowed to return again next year, same time, same place.

We didn’t see Mariner or any other herons while out on Eggemoggin Reach. After checking Mariner’s tracking data that evening, it showed she spent most of the day at a freshwater wetland on the mainland. Soon, she will depart Maine and head south for the winter, and we can’t wait to see where she ends up and the path that takes her there!

You can track Mariner’s movements online by following the instructions here: mefishwildlife.com/trackherons. The map below shows her movements from the past two weeks:

Many thanks to our captain, Andrew Washburn, for a glorious day on the sea!