June 20, 2019 at 8:44 pm

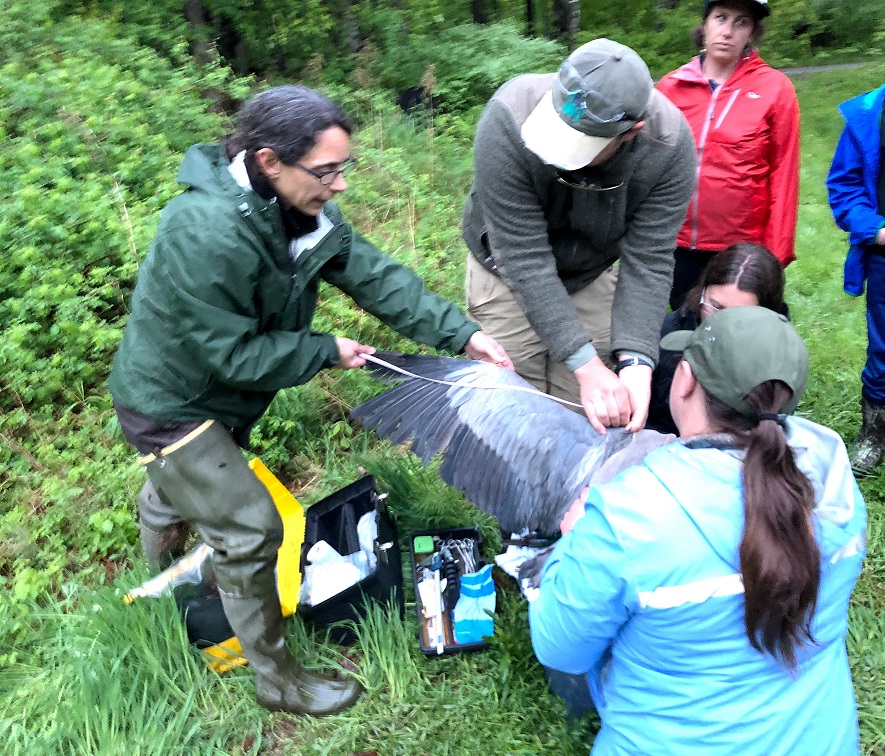

For nine students at Harpswell Coastal Academy, Wednesdays in May meant donning knee-high boots, venturing to a nearby wetland, and hoping for signs a hungry great blue heron had been there. As part of a spring class elective, these students were dedicated to helping MDIFW ultimately tag a great blue heron with a GPS transmitter as part of an ongoing project to better understand heron habits in Maine. For several weeks they monitored a small shallow pond with a game camera. Their first critter on film was a raccoon. Then there were ducks, egrets, deer, and finally a great blue heron. Their minnow traps were set in the same wetland and they checked them every couple of days to determine which type of traps worked best – silver, white plastic, or black-coated metal? Their catch would eventually be used to create an irresistible feeding bin for a heron.

-

Harpswell Coastal Academy students collecting baitfish from minnow traps. -

Harpswell Coastal Academy students fill a bait bin with baitfish.

Volunteers with the Harpswell Heritage Land Trust were simultaneously monitoring another potential site; and eventually both sites had herons feeding regularly out of the bait bins. It was time to outsmart a heron and capture one for attaching a transmitter. The plan was to have traps set at first light. The students wanted to be there, so with no hesitation they agreed to sleep over at the school the night before. Their teacher, Amanda Sommi, helped the biologists get set up at “o-dark-hundred,” otherwise known as 3:30 am. If and when a heron was caught, she would call the students to come over and see.

Sure enough, at 4:30 am a great blue heron flew in to the wetland. Biologists were practically holding their breath for the next 20 minutes as they watched the heron slowly make its way along the wetland edge to the bait bin encircled by humane traps. At 4:50 am, the heron had stepped in a trap and within less than a minute it was safely contained in a biologist’s arms awaiting a GPS transmitter to wear as a backpack. The students came out with another teacher and were able to watch biologists take measurements, a blood sample for sexing, and attach a leg band and transmitter. Most importantly they had the chance to see the heron and all its fine details up close – the decorative feathers, the yellow eye, the dagger-like bill, the long skinny toes, and the impressive wings. Although less than five pounds in weight, a heron’s physical beauty is awe-inspiring. This heron turned out to be a female and the students and volunteers named her "Harper."

-

Measuring the wing span. -

Measuring the culmen or beak length.

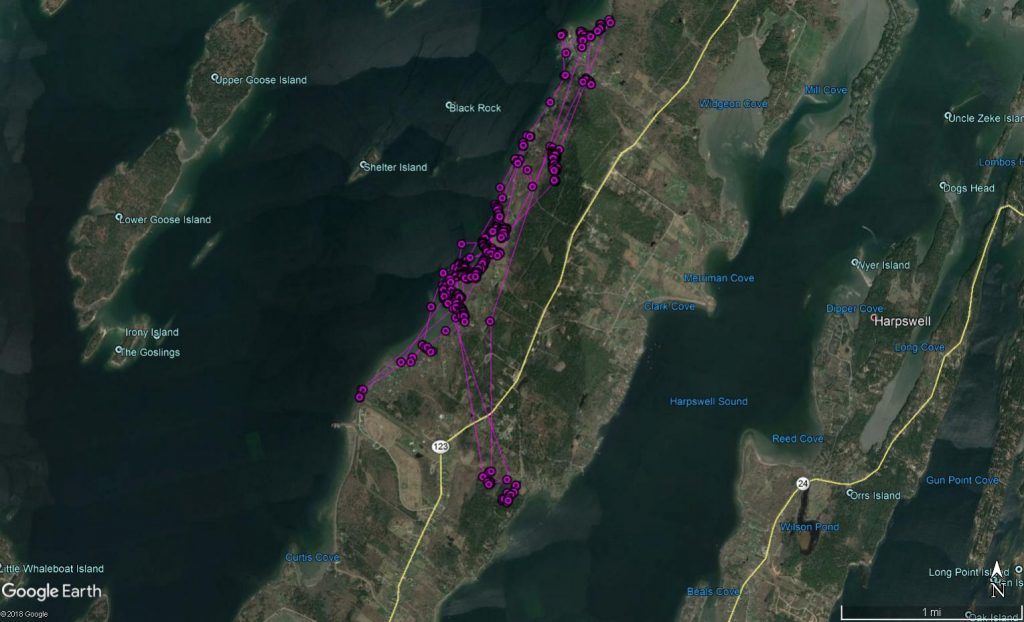

Upon release, the heron’s transmitter logs GPS locations as often as every 5 minutes and downloads the data to a website where anyone can track the bird’s movements over time. As with any wild animal that undergoes capture and handling by humans, there is a chance the animal may be affected and not act normal or become susceptible to predation. Biologists monitored Harper’s movements very closely for the first ten days and saw she was moving around and visiting a variety of good potential feeding sites within three miles of the capture site. This was great news.

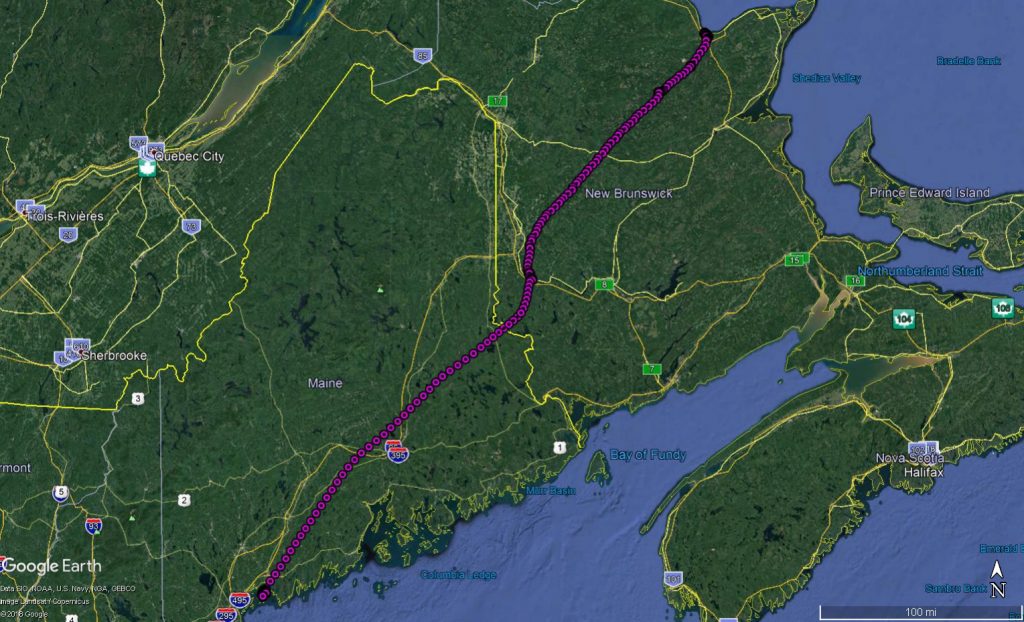

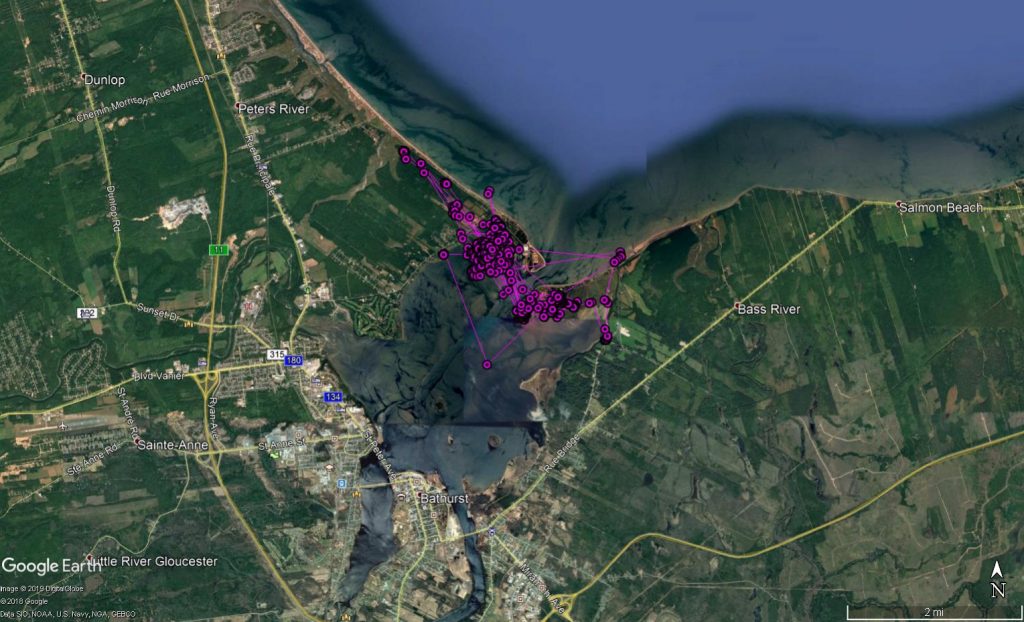

Then came the unexpected. After two days of not obtaining data downloads from Harper's transmitter, the next download showed her in New Brunswick, Canada! Between June 9th and 11th, the heron had flown over 340 miles to an estuary of the Nepisguit River in the city of Bathurst. We do not know why she moved so far to the northeast. Our current hypothesis is that Harper was originally from (hatched in) New Brunswick and that she wintered further south than Harpswell. She may have decided not to breed this year and thus took a long layover in Harpswell on her way back north. Perhaps the warm weather over the weekend was the final push to return north. We may never know the true reason, but we can certainly continue to watch Harper’s movements and her story that unfolds over time. Hopefully she will return to Maine, even if just on her migration north or south.

To track the movements of Harper or our other two tagged herons, Cornelia and Nokomis, visit this website for instructions. Also be sure to follow the Heron Observation Network of Maine on Facebook to receive timely updates throughout the year.