June 3, 2021 at 8:31 am

As I carefully place the last foothold trap into the shallow water next to the bait bin, I am startled by the squawk of a great blue heron as it briefly touches down on an overhead branch then lifts off again. We’d better get out of here if we want the heron to return to eat its breakfast – a smorgasbord of minnows and shiners swimming in a small tub – easy pickings for a heron. It is 4:15 am, and dark enough to still need headlamps to navigate back to our truck. My technician, Brittany Currier, and I roll the windows down so we can hear a trap when it’s triggered since we are not confident we will see anything even with binoculars.

Now the waiting begins. Last week we waited all day for a heron to come back to the trap site, with no luck. As in most wildlife field work, heron trapping is hardly predictable. Today, we are in luck because less than a half hour later, a heron flies in to the small pond, just feet from the bait bin and set traps. We hold our breath as we stay still and quiet, waiting for the heron to slowly step closer to the bait bin to strike at a fish contained within. Within two minutes it happens: the heron takes one step closer, we hear the trap close, and see the bird extend its wings. We are out of the truck as quick as a flash, racing across the field towards the heron. I am pretty sure I’ve never run that fast in my life! Brittany grabs the net, places it over the heron to keep it from struggling, I work a pillow case beneath the net and over its head to keep it calm, then we bring it to the shore to take its foot out of the trap. Now we can breathe.

For the last three weeks, a team of high school students and teachers from Harpswell Coastal Academy, local volunteers, and IFW staff have been catching bait fish and transferring them to bait bins hoping to attract a great blue heron to target for tagging with a GPS transmitter. Equipped with bright orange Home Depot pails and a bait fish ID sheet, volunteers stocked the bins daily to make sure hungry herons always had an enticing meal waiting for them. Our game cameras let us know when a heron fed from the bin. It got to the point where the herons seemed to be waiting for the bins to be stocked each day.

The heron we caught on this fine May morning is large and displaying gorgeous colors indicating it is likely a breeding male. We take a blood sample to definitively determine its sex because there is a lot of overlap in size between males and females. We are hopeful that the heron in our hands is an island-nesting bird. There are several islands in Casco Bay that host heron colonies, or nesting areas, which is why we decided to trap a heron in Harpswell. We’ve seen a significant decline in the number of nesting pairs on our coastal islands, and want to learn more about their movements and habits to help determine what may be contributing to the decline. We tagged a heron here in 2019, but that heron, named Harper, ended up flying to New Brunswick, Canada, to nest. Did I mention that wildlife can be unpredictable?

to temporarily keep the feathers out

of the way. Note the bright orange bill

and eye! Photo by Liz Incze.

The GPS transmitter is carefully attached to the heron using a backpack design made out of Teflon ribbon. Locations are logged as often as every 5 minutes, and every evening the transmitter communicates via cell towers to download the last 24 hours of data to an open-source website, movebank.org, where anyone can view the heron’s movements. There is a solar panel on the transmitter that recharges the battery, making it last for multiple years. The transmitter on Cornelia, one of the first herons we tagged in 2016, is still functioning five years later.

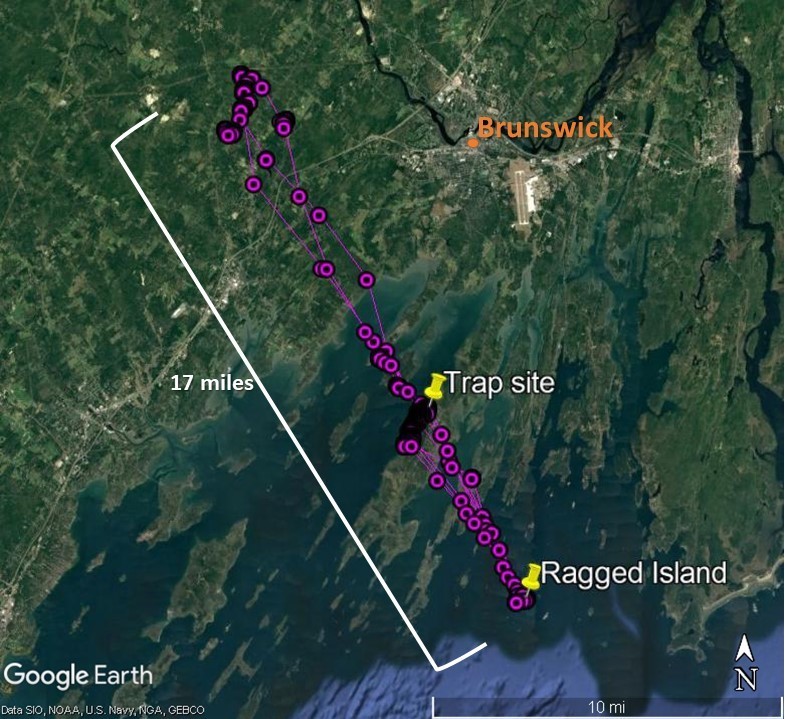

The heron was released at 6am, and we’ve been following its movements very closely since then. [Check out this video of its release]. After nearly a week of data collection, we can see that this heron is nesting on Ragged Island, a known heron colony. We have watched it go back and forth between Ragged Island and what appears to be a favorite feeding area along the west shore of central Harpswell, very close to where it was trapped, over 6 miles from its nest. It also has occasionally flown even further, 17 miles one way, to feed in a stream in Durham. Already, this heron has broken the record of our tagged herons for distance flown from its nest to feed. How else will this heron surprise us, and what new lessons are in store for us?

After receiving the DNA results confirming it’s a male, the students at Harpswell Coastal Academy chose a name for our first tagged island-nester: Ragged Richard. We are excited to continue watching Ragged Richard’s movements to discover any differences between our island and inland nesting herons, and any clues why herons have been declining along the coast. You can track Ragged Richard’s movements by following the instructions here.