Home → Maine Poems → Maine Poet Laureate, Wesley McNair

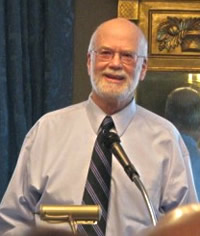

The Remarks of Maine Poet Laureate, Wesley McNair

The Blaine House, Augusta, April 20, 2011

Photos credit: Patricia O'Donnell

Listen to Wesley McNair speech as you follow along with the text below or download the PDF version. [92 KB] This file requires the free Adobe Reader.

In normal times, a newly appointed Poet Laureate would stand up here at the podium, read some poetry, and call it a day. But these are not normal times. As you know, this is a period of political turmoil and division in the country, and in our own state. Yet despite the turmoil, we Maine people have gathered together for this event in the Governor's house, which is also our house, because we understand that poetry has a meaning and importance that transcends our politics. I want to say a few words on this occasion about why in this troubled period of ours, poetry is so important.

We turn to poetry whenever we come to one of life's milestones – a wedding, say, or the death of a loved one -- because it expresses an emotional truth we can find nowhere else. Poems are read at school convocations and college commencements because they remind us that no human journey is complete without hope. I am a poet because creating poems opens my imagination to the wonder of the world we've taken for granted, or called by the wrong names. And I'm drawn over and over to poetry's abiding spirit of affirmation, which is the spirit of all art, everywhere, whether it be sculpture, music, or paintings on a wall. The ultimate goal of every single poem is a change of mind or a change of heart, not only for the reader but for the writer. You can't write a poem without experiencing that change yourself, and if you've written enough of them, you come to realize also that every poem is a love poem, because every poem, no matter what its subject or mood, asks us to explore, cherish and care about something that might otherwise be lost.

It's amazing, when you think about it, that such vision and authority could come from the little poem, which is, after all, just a few sentences grouped around an insight. Left without fanfare on the page, a poem is passed from one reader who discovers it, to another who pins it up so others can see it, to still another who learns it by heart. In this gradual way the poem acquires a life that lasts long after the fanfare of the political moment, just as in the end, the names of our greatest poets outlast those of the politicians, whatever their party affiliation.

That Maine has produced so many of America's great poets should be a source of pride for all of us. The tradition they began gives me inspiration as I undertake the work I hope to do as Poet Laureate. I say work, because in this period of political discord, which has now found its way into the arts, our state needs something more than a ceremonial spokesman for poetry and literature. I will be an engaged and active laureate. At a time in our politics when the value of art itself seems to be in play, I intend to play harder.

I will take my direction from three poets of Maine's past who are the best loved and most widely known, namely, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edwin Arlington Robinson and Edna Saint-Vincent Millay. As you'll remember, these three poets managed to be both complex and accessible in their work – not an easy combination to pull off. They did not confine themselves to some specialized school of writers or to an academy; instead, they wrote about, for, and to readers from all walks of life, and they sold their collections in the tens of thousands. Easy for them to do, you poets might say – they lived in a different day and a different culture. And saying so, you might be right. But I sometimes wonder if we poets have done enough to break free from our literary cliques and carry our vision to general readers, who need it more than the literary groups we tend to surround ourselves with. Poetry belongs to our fellow citizens, too. Which of us poets, after all, has not had that sinking feeling when we find our audience at a reading consists entirely of other poets? As Billy Collins once remarked, it's a bit like coming on stage as a ballerina to discover that everybody in the audience is wearing a tutu.

To bring poetry to the people of Maine, I will undertake two projects in the initial year of my five-year term. The first project, beginning this fall, will be a series of readings called "The Maine Poetry Express," a "train" that begins in our northernmost town of Fort Kent, and makes it way south by way of "stops" that feature group readings given by poets in all the regions of Maine, including what are called "underserved areas," from north to south and from east to west. The public will be able to purchase broadsides of work by the participating poets at each stop, and follow the train's journey online at the Maine Writers and Publisher's Alliance website, or on the new Maine Poet Laureate Facebook page. As the Maine Poetry Express travels the state over a period of months from stop to stop and publicity grows, so will the interest in poetry grow, along with the pride that each region takes in its own featured poets.

My second project as Poet Laureate will begin immediately and continue throughout my tenure. I will sponsor a new column for newspapers across Maine featuring one previously published poem a week by a Maine poet from the present, or from our illustrious past. The name of the column will be Take Heart: A Conversation in Poetry, or more simply, Take Heart. With the invaluable assistance of Joshua Bodwell, Director of MWPA, I've already secured commitments to this column from all the major daily newspapers in the state, and more than a dozen others from the coast to the far north, and every location in between – well over 20 newspapers in all. The Maine Sunday Telegram and its sister newspapers, The Kennebec Journal and The Morning Sentinel, have offered to add something special to their printing of Take Heart – that is, a photo of each poet whose work appears in the column, together with a profile written by the Sunday Telegram's widely respected arts reporter, Bob Keyes.

During the first week of May, Take Heart will make its first appearance in Maine newspapers. I want to credit David Turner, my special assistant at MWPA, for the work he has done with permissions and other logistics to make the column run smoothly. And by the way, as a gift to each of you in the audience, Josh has printed a special keepsake edition of the first installment of the column, with a little color added for drama. This keepsake has been signed and numbered by the poet, Stuart Kestenbaum.

Let me add this final point about Take Heart. You'll remember I mentioned that in an earlier day, tens of thousands of readers read the poems of Longfellow, Robinson and Millay. But we no longer need to wring our hands about that. The Maine poets of Take Heart will easily reach tens of thousands of readers once again, and even more readers when we establish the option of email subscriptions. Over time, favorite poems from the column will start appearing on the doors of family refrigerators and professional offices, and people will email them to friends both inside and outside the state. By putting poetry directly into the laps and the laptops of readers everywhere around us, we'll remind our fellow Mainers that poetry is not only for the special days of weddings, funerals and commencements, but for every day of our lives.

There will be other initiatives in my future as Poet Laureate, and I'll be announcing them one by one as I go along. But for now, I'll conclude with a poem that underscores the themes I've been talking about here: not only the all-important connection between poetry and the people, but that sense I mentioned earlier of poetry's affirmative and loving vision.

This poem takes place in a Maine Grange Hall in my town of Mercer. A few winters back a woman in Mercer called me up and said some Grangers were getting together at their next meeting to demonstrate and talk about their hobbies, and she wanted to know if I'd be interested in attending that meeting myself to read some poems and talk about my hobby of poetry writing. As you can imagine, I had mixed feelings about this. But I went along anyway, and something wonderful happened. I was won over by these people at their community supper downstairs in the Grange Hall, and their meeting afterward upstairs, during which they pledged allegiance to the flag and conducted their Grange rituals, wearing their long, blue sashes. It wasn't that I didn't know the people outside the Hall. I knew Francis and Dolly Lee, a couple you'll meet in the poem, and I knew the Grange Officers, apart from the roles they were playing, and I knew the two mentally challenged men who were there that night. But somehow they all became transformed for me under the lights of this place. And to top it off, when I read my poems, they listened thoughtfully and seemed to like them. And that's how the word "heaven" gets into this poem, which is called "Reading Poems at the Grange Meeting in What Must Be Heaven."

How else to explain that odd,

perfect supper – the burnished

lasagna squares, thick

clusters of baked

beans, cole slaw pink

with beet juice? How else

to tell of fluorescent

lights touching their once-familiar

faces, of pipes branching over

their heads from the warm

furnace-tree, like no tree on earth --

or to define the not-quite

dizziness of going

up the enclosed, turning

stair afterward to find them

in the room of the low

ceiling, dressed as if for play?

Even Dolly Lee, talked into coming

to this town thirty

years ago from California,

wears a blue sash,

leaving each curse against winters

and the black fly far

behind. And beside her

Francis, who once did the talking,

cranking his right hand

even then, no doubt, to jumpstart

his idea, here uses his hand

to raise a staff, stone silent,

a different man. For the Grange

meeting has begun, their fun

of marching serious-faced together

down the hall to gather

stout Bertha who bears the flag

carefully ahead of herself

like a full

dust-mop, then

marching back again,

the old floor making long

cracking sounds

under their feet like late

pond ice that will not break --

though now the whole group stands

upon it, hands

over their hearts. It does not matter

that the two retarded men, who in the other

world attempted haying for Mrs. Carter,

stand here beside her

pledging allegiance in words

they themselves have never heard.

It does not matter

that the Worthy Master,

the Worthy Overseer

and the Secretary sit back

down at desks

donated by School District

#54 as if all three were

in fifth grade: everyone here

seems younger – the shiny baldheaded

ones, the no longer old

ladies, whose spectacles

fill with light as they

look up, and big Lenny

too, the trucker, holding the spoons

he will play soon

and smiling at me as if

the accident that left

the long cheek scar and mashed

his ear never happened. For I

am rising

with my worn folder

beside the table of potholders,

necklaces made from old newspaper

strips and rugs braided

from rags. It does not matter

that in some narrower time

and place I did not want

to read to them on

Hobby Night. What matters is

that standing in – how else

to understand it – the heaven

of their wonderment,

I share the best

thing I can make – this stitching

together of memory

and heart-scrap, this wish

to hold together Francis,

Dolly Lee, the Grange Officers,

the retarded men and everybody

else here levitating

ten feet

above the dark

and cold and regardless

world below them and me

and poetry.