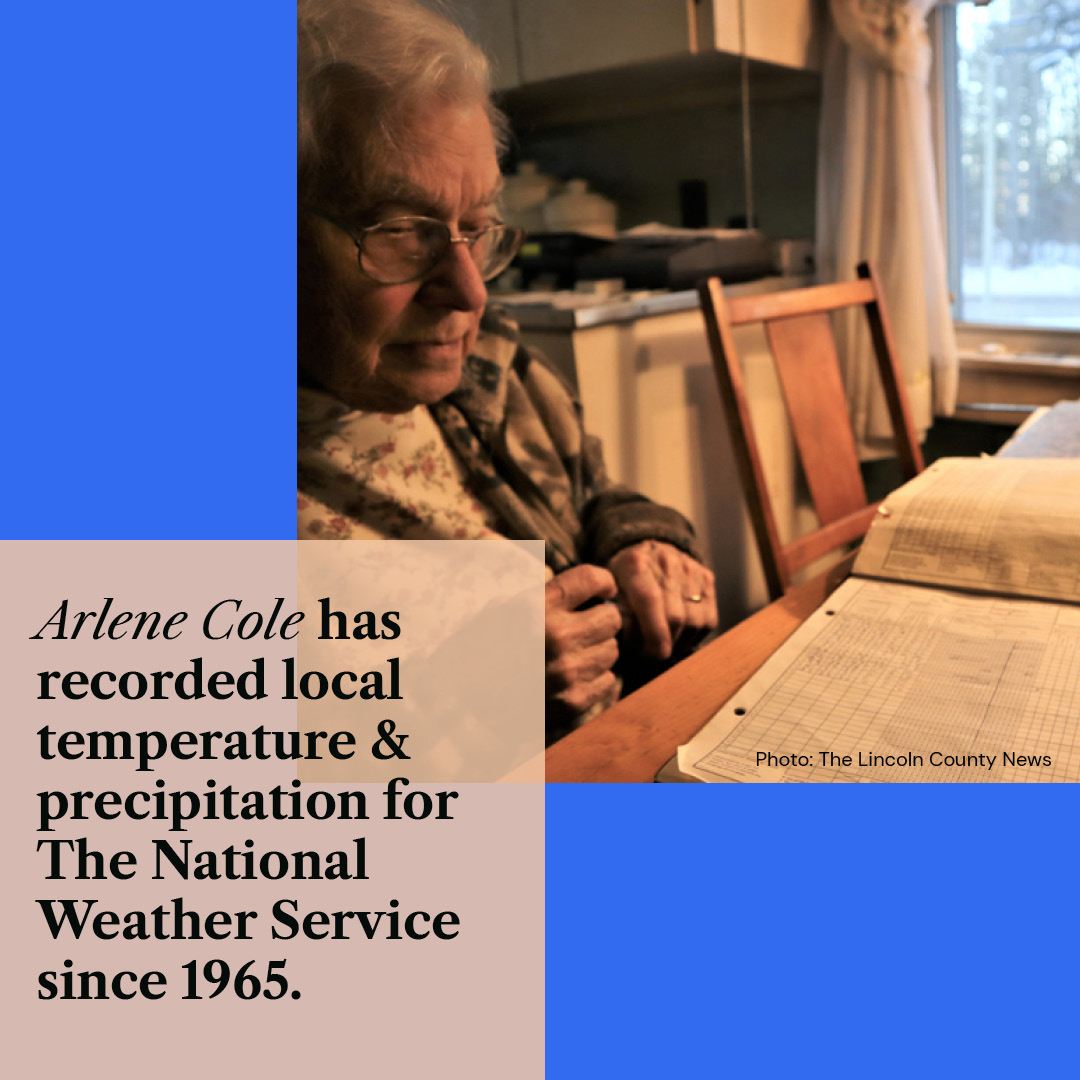

Newcastle's Arlene Cole: NOAA Weather Observer Since 1965

Every day at 5pm, Arlene Cole of Newcastle records the temperature and measures precipitation levels. Every month, Arlene sends her findings to the National Weather Service, a division of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

She’s done this since 1965.

Arlene is a member of the The National Weather Service Cooperative Observer Program (COOP), the “nation's weather and climate observing network of, by and for the people.” More than 8,700 volunteers provide weather condition observations taken from farms, urban and suburban areas, National Parks, seashores and mountaintops across the country. The observational data helps NOAA measure long-term climate changes.

In fact, Arlene received a letter from NOAA in 2010, thanking her for her critical role in aiding in their understanding of how to solve problems related to climate change, commerce, transportation and agriculture.

- Are you a life-long Mainer?

My residence has always been in Lincoln County. I was born on July 10, 1930 at the Lincoln County Memorial Hospital on Elm Street in Damariscotta. When I was two weeks old my father brought my mother and me home to the farm in Jefferson in his Model-T – about ten miles.

- What is the backstory for how you started sending recordings to NOAA?

I started with NOAA 57 years ago this coming May. Jefferson resident Nancy Rawlings had a NOAA weather station at her home on the Bunker Hill Road and provided the weekly temperatures to the Lincoln County News. I would copy them for my records. I had a 5-year diary I had started in 1957 with my own thermometers. When Nancy Rawlings died in 1965, her husband Charles (Chuck) Rawlings suggested my name to NOAA. This weather station was put in at my place May 12, 1965.

- What do you monitor for NOAA, and how do you do it?

For equipment I have thermometers that give me the temperature now and the high and low temperatures since I set them last. At first, I visited the outdoor station every day, but now I can read the information from my kitchen counter. I have two rain gauges, two white boards, a 24 inch measuring stick marked in tenths and a stake that can be inserted into the ground each fall so that numbers 1-60, an inch apart, can be read. My time of the day to measure and record is 5 pm. At 5 pm I record the high and the low of the past 24 hours and what it is at 5 pm. If it precipitates, I write down what kind of precipitation came down, when it came, and how much of each kind. If it happened when I was sleeping at night, I mark a wavy line when I estimated it occurred. I record the depth of snow on the ground, any fog, thunder, hail, or damaging wind. I mail my recordings to NOAA at the end of each month.

- How did growing up on a farm shape your interest in weather?

By the time my father inherited our farm, about 1912, the family had acquired about 100 acres. Our father loved his farm. It was a subsistence farm where we were pretty much a contained unit. But there was a lot of work for us. He cut wood to burn, ice to cool, gardens and animals for food. He had to pay the town tax, buy shoes and clothes and flour, sugar and molasses. We made out fine. And we did not work all the time. My sister Margaret and I scouted every nook and cranny on the farm. Our father said that some people did not like to have kids walking over their land and we should stay on our land. He smiled and said he thought we might be able to get by with the 100 acres! Our land bordered on Dyer Long Pond. As soon as he was assured we could swim, we had that area to explore, too.

Of course I was interested in the weather. We lived the seasons and the weather every day.

Are you interested in contributing to climate science? We have a list of resources to get you started.