How a Marine Geologist Measures Maine's Coastal Changes

Peter Slovinsky has a life-long fascination with the coast. Growing up, he spent hours digging in the sand, fishing and surfing. In his 5th grade yearbook, he said wanted to be a “Coastal Engineer” when he grew up.

He got pretty close.

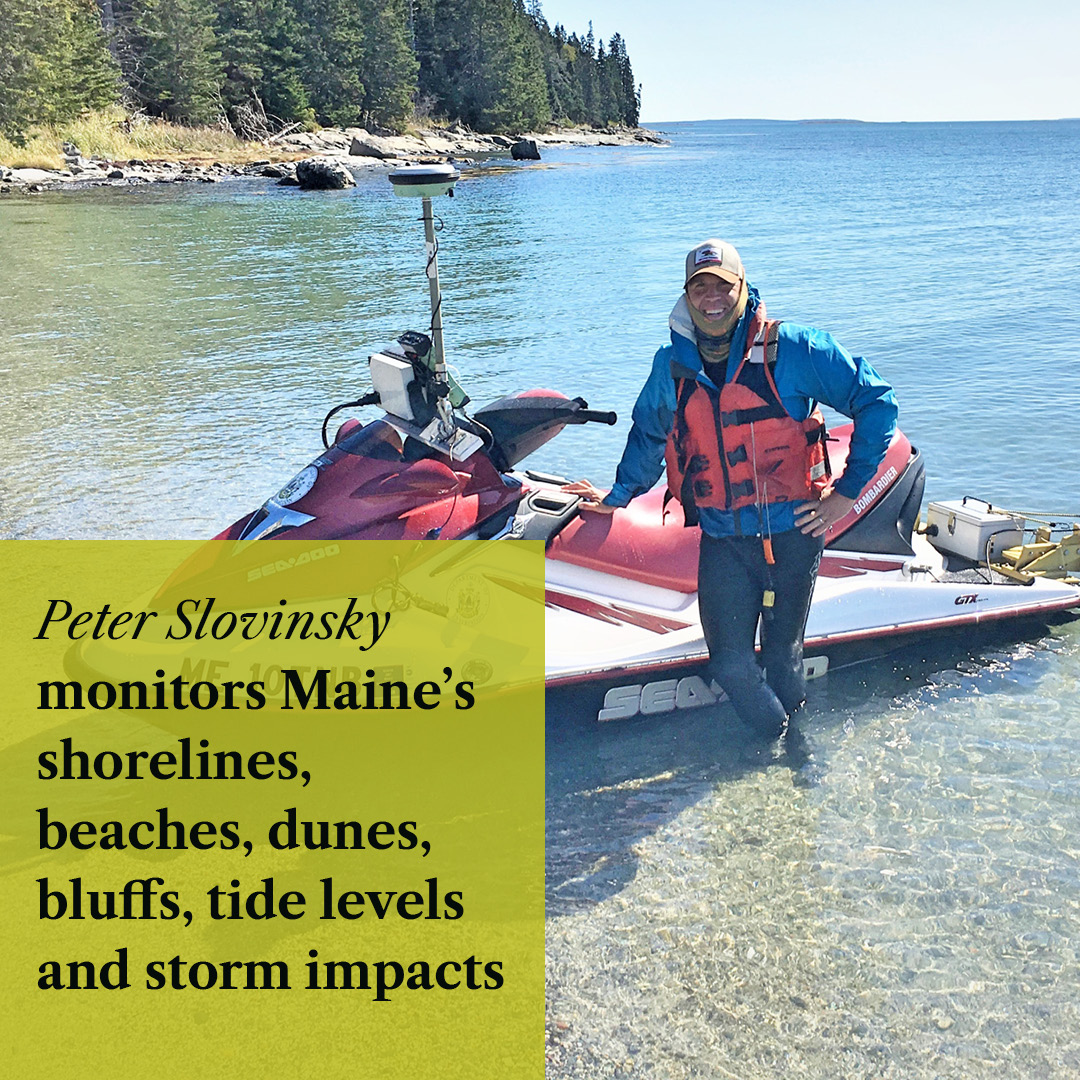

Today, as a Marine Geologist at Maine Geological Survey, Peter analyzes Maine’s shorelines, beaches, sand dunes, bluffs, tide levels and storm impacts. Many days, he zooms around on a personal watercraft outfitted with cutting-edge GPS and depth sounder technology to map and measure shoreline change trends.

Peter’s work is key in understanding climate change impacts on Maine’s crucially important coast. Sea-level rise and erosion is projected to shrink Maine’s total dry beach area by at least 43% by 2050. This would decrease visits by more than 1 million people and lower annual tourism spending by $136 million. This is why the Maine Won’t Wait climate plan outlines strategies to reduce emissions tied with warming ocean temperatures, erosion and rising sea levels.

- What does a typical day look like for you as a Marine Geologist?

There really isn’t a “typical” day, which is one of the things that makes my job so much fun. There’s a lot of meetings and computer-related work, but also a lot of time in the field. One day, I could be measuring how much a beach or dune is eroding, and the next, visiting an eroding bluff or a living shoreline, or collecting bathymetry on our Nearshore Survey System. I could be analyzing tide gauge data to see how water levels are varying seasonally or how big the storm surge was from the last storm we got, or quantifying shoreline change rates along Maine’s beaches. You could also find me meeting with a community to discuss their vulnerabilities to a variety of coastal hazards and learn about different local adaptation strategies, or working with a variety of stakeholders on furthering regional and state level adaptation efforts.

- How did you become interested in climate science?

I’ve always been interested in climate science, but my interests really took off when I started working with communities on vulnerability to coastal storms and sea level rise. I really enjoy making the connection between understanding vulnerabilities and impacts from climate change and driving change at the municipal, regional, and state levels.

- Tell us about the personal watercraft technology your team uses!

When I started working at MGS in 2001, I learned of a program that monitored beach profiles at select beaches in southern Maine, but only to low tide. This left a huge portion of the beach offshore “unpictured” in terms of understanding what was happening to sand in response to storms and seasonal changes. To better understand what was happening in this “nearshore” area, in 2003, we got a grant from the Maine Technology Institute to develop what we called the Nearshore Survey System, or NSS. It uses a personal watercraft outfitted with a very precise GPS and a high-precision depth sounder to map nearshore bathymetry, or the topography of the beach. We’ve used it to map the bottom of rivers for bridge reconstruction, map tidal current patterns, map areas where tidal inlets are dredged, and also map how sediment moves when it is placed in the nearshore environment as beach nourishment. Over the years, we’ve updated the system as technology has evolved.

- Why is it important to understand what is happening to sand in responses to storms and seasonal changes?

Understanding sand movement in response to storms and seasonal changes help us manage our beaches and dunes in the face of storms and sea level rise. For instance, we know that winter storms can erode a big portion of a beach, but we’ve learned that the eroded sand usually is moved into offshore sandbars and is returned to the beach in the following spring/summer season. So just because a beach looks eroded in the winter doesn’t mean that it lost all that sand – the sand is still part of the beach system, just under the water during the winter season. This is what we call the “seasonal beach cycle”.

- What do you think more people should know about climate change in Maine?

That it’s something that is impacting us now, today, not something that will only impact future generations. Sea level rise is something that most folks think won’t impact them in their lifetimes, but even small amounts change how storms and flooding impact our coast. For example, we’re already seeing sea level rise increasing the number of days over a year that high tide flooding occurs in low-lying areas of our coastal communities. And even small amounts cause coastal storms to erode areas of beaches, dunes, wetlands, and bluffs that haven’t been eroded in the past. We’ve taken big steps through the formation of the Maine Climate Council and Maine Won’t Wait efforts, but there’s still a lot to do!

- Do you have any advice for people who want to get involved in climate science?

Two words: do it! Understanding how climate change is impacting your own backyard is so important and makes it much more of a local issue. And we really depend on citizen-based monitoring programs to understand everything from how beaches are impacted by storms, to how water quality at swimming beaches varies over the course of the year.

Find a list of citizen-science initiatives in Maine here.

- Given your area of expertise, do you have advice for Maine's coastal residents?

The first thing to do is to understand your vulnerabilities to coastal storms and climate change. The second, is to develop actionable adaptation strategies. Adaptation strategies along the coast really fall into four different categories – avoid, adapt, protect, and retreat. Questions to consider:- If you’re building a new house along an eroding coastal bluff, can you set it back as far landward as possible?

- If the dune in front of your house gets overtopped a lot during storms, can you restore your dune to a higher elevation, thus maintaining its natural protective function?

- If your house is in an area that regularly floods during coastal storms, can you move it to higher ground? Or if not, can you elevate it?

">

MGS has developed a Coastal Property Owner Guide to help coastal property owners understand vulnerability and develop strategies to address those vulnerabilities in bluff, beach and dune, and marsh environments.

To learn more about sea level rise, visit our Climate Science Dashboard for interactive data dashboards and links to more resources.